My novels about early Hollywood are verbal time machines designed to lift the reader into a bygone era. When that happens to be the silent film era, it can be a challenge finding the right fictional “voice” for a character, especially if he or she is based on an actual person.

Right now I am trying to find the right speaking voice for G.W. “Billy” Bitzer, the pioneering cameraman who worked at American Biograph in the first years of narrative filmmaking. He was born in Boston in 1872 (1874 by some accounts), but his parents were German immigrants. His father was a blacksmith who specialized in making leather harnesses, so I imagine his son picked up a lot of old world idioms and a foreign-inflected approach to speaking English.

But the truth is, we know very little about that. His own autobiography has been carefully proofread to read like standard all-American prose, and nowhere does he refer to his adventures in mispronunciation or to stumbling into any cultural minefields.

Many of his colleagues in silent film wrote about Bitzer, from D.W. Griffith himself and Mary Pickford, to Miriam Cooper and fellow cameraman Karl Brown. Clues about how he sounded when he spoke, though, are general at best.

There’s a wonderful Warner Bros. short from 1934 based on a story by Bitzer about an aging cameraman who listens when “The Camera Speaks.” But that on-screen veteran is only an actor surrogate for the real Billy Bitzer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NVQb4fRLcJo

I did not have that trouble with some of the icons of silent film who went on to a career in talkies. Sound movies can be a good resource for finding speech and breath patterns, intonations and accents, even in scripted dialogue. But they do not help much with unique idioms, beliefs, and personal quirks of speech.

For “The Ben-Hur Murders,” I found it easy to mimic Norma Shearer’s vocal patterns and infer much about her personality through the artifice of her sound films. It was all there in the choices she made — from the choice of the material itself to the decisions she made as an actress to get at “the truth” of her roles. I assumed that she brought a similar style and self-awareness to her performances in public.

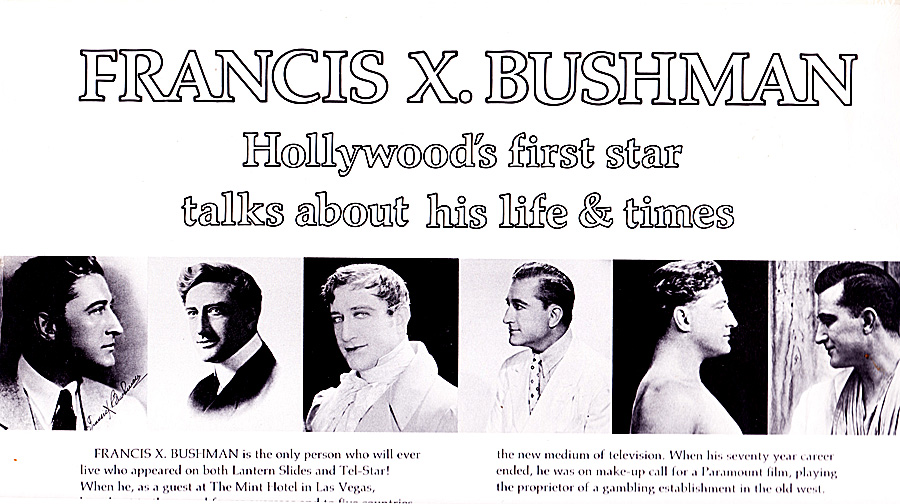

Francis X. Bushman was slower in coming. His style of acting was to adopt an often-somber and classic persona that concealed his own humanity. No one would believe him as a character if all he did was pronounce his dialogue like a stuffy orator with the studied diction of a grand thespian.

Bushman was indeed of that old school of trained classical actors who carried forth a certain grandiloquence of manner over to their real life. From all accounts, Edwin Booth cultivated that air of bemused superiority, too, as did the Barrymores, John Carradine and Vincent Price in our own age.

Luckily, I came upon this audio recording of Bushman talking in his later years about his life and career. This vinyl LP record is where I discovered he had a habit of underscoring his own statements, as if his tale were so astounding even to himself that he doubted the ability of the listener to grasp it.

“Can you believe it?” he would interject, or, “Get the point?” These and other similar asides peppered every one of his remembrances. This was clearly more than an older man’s idiosyncrasy, and it differs from today’s stoner convention of throwing “like” into every sentence for fear of actually having to take responsibility for a declarative assertion.

Here is a cutting from Chapter Five of “The Ben-Hur Murders,” in which the narrator returns a borrowed chariot on the set of “Ben-Hur” and encounters the singular Francis X. Bushman in the flesh …

***

The horses and chariots were kept in a livery yard under a patchwork tin roof outside the north end of the track. … The studio guard was probably some director’s son, happy to earn a little pocket money on a Saturday while his pals were out playing ball or taking in a Hoot Gibson western. He signaled for me to slow my team to a walk, then raised a hand to his freckled mouth to be heard over the racket. “What happened to Mr. Fisher?”

“I’m bringing it back for him. Can I leave it here?”

He shook his head violently and pointed deeper inside the stables. “See that fancy pink chariot down at the end?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s Mr. Bushman’s rig. Leave her next to that.”

“Mr. Bushman? You mean Francis X. Bushman?”

The boy pursed his lips and squeezed his skinny shoulders in a bored shrug before waving me along.

My promise to Mrs. Addison! What a dummy! Here I had been carrying her silly autograph book all morning in my back pocket, and it never crossed my mind to ask Ramón Novarro to sign it for her. Maybe if I got her Francis X. Bushman’s signature I could be done with the whole mortifying business.

Bushman’s so-called “pink rig” was actually lavender, which made sense to me because I had read somewhere that lavender was his favorite color. He was famous for his custom-made cigarettes wrapped in lavender paper, and he rode around Hollywood in a lavender Marmon limousine with his name embossed in gold on both sides.

His chariot turned out to be a real beauty. It was decorated with swirling vines surrounding a raised figure of a shiny black peacock. No one seemed to be around, so I tied off my team and went to have a closer look. The carriage was wider and higher than my little two-horse parade car. They called these four-horse racing rigs quadrigae in Roman times. Each was sturdy enough to be pulled along at full gallop by a team of runners strapped haunch-to-haunch with a shoulder-blade yoke. From one wheel hub to the other, the axle stretched nearly eight feet. The wheels on this one had fancy black spokes and came up to my ribcage. The bed rested in a welded metal frame, though the wagon itself was just wooden panels topped with a curved hardwood rail.

I leaned over to give it a rap and suddenly a fierce head came shooting bolt upright from the other side. It resembled the stone giant outside the spina, drained of all color and wearing an expression as stern as death. This time, however, it spoke.

“What can I do for you?”

“Sorry. … You wouldn’t be Mr. Bushman, would you?”

“If you’re here for an interview, you will have to be brief. I am a moving target. You think you have me in your sights but not for long. By the time your prose appears, I’ve accomplished a hundred new things and I am a thousand miles away, and your fish-wrappers are blowing across rails a dozen station stops behind me.”

It was him all right. While I didn’t know a thing about Ramón Novarro before I met him, the whole world knew something about Francis X. Bushman. He had been making movies since 1911, and had starred in two hundred feature films. He was said to be earning a million dollars a year at one point, and with his wavy brown hair and athlete’s physique, no one challenged his billing as “the handsomest man in the world.”

He was the world’s first male sex symbol, receiving marriage proposals from every quarter of the globe. That all ended abruptly, though, when he was caught in an affair with his “Romeo and Juliet” costar. Then the newspapers found out he had a wife living back home in Baltimore. The Bushmans bred Great Danes on an estate there, not to mention five children. The marriage ended shortly after that, and Francis married his Juliet. But female movie-goers had already moved on to a new breed of sex symbol like Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert.

Bushman’s contract with Metro was part of the baggage included in the M-G-M takeover. When he was cast in “Ben-Hur” as Messala, the villainous Roman officer, magazines called it a potential “comeback” role for “the old man,” which is how everyone except Mrs. Addison thought of Francis X. Bushman in 1925. He was, after all, forty-two years old.

“No, sir. My name is Grover. My landlady, Mrs. Addison, says she’s your biggest fan.”

“Indeed? No doubt a charming lady with sophisticated tastes.”

“Yes, sir. Well … maybe.”

“Don’t tell me — you are new at this studio?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Everyone is new except me, it appears. Do you know I used to have to apply a fake mustache and put on glasses when I went to a store? Everyone knew my face. I used to be known by all the producers and casting directors in the world. But they’ve moved along now, get the point? Now I turn out for a role and some pink-cheeked boy or flat-chested college gal asks me what I’ve done.”

“I’m not from casting or anything. I’m just one of the horse tenders.”

“Well, Grover, nothing to be ashamed of there. That is honorable work, yes indeed. I always adored working with animals. When I was growing up, I adopted animals of every sort. Rabbits, snakes, finches, fish. I loved them all, and they would all come to the front of their cages and aquariums when I walked in the room. I would get up before dawn and run down to Lafayette Market, and everyone saved me scraps and whatever hadn’t sold, you see, because they knew I had all these animals to feed. It was the most astounding thing. I was only nine. But everyone loved me, because I was such a beautiful boy. … What do you know about these undercarriages?”

He must have seen my sudden confusion.

“Look here,” he said, signaling for me to join him beneath the chariot. He pointed out some holes in the assembly that had been drilled to raise the axle blocks three or four inches higher. “Why do you suppose they repositioned the axle?”

“Make it faster?”

“Smart lad. That is exactly what I was thinking. Someone probably thought they weren’t swift enough in Italy. Of course, since then they added the metal frames. They were all wood at first, and very fast, but that was a mistake and it cost one poor man his life. I saw it.”

He motioned for me to come closer, as if to share a secret. “Don’t look right away, but when you get a chance, there are two men watching us from a post behind you. Tell me if you know either of them.” Then he pulled back and straightened to his full height. He must have stood six feet, which was taller than most men in those days. Without a beat, he continued to speak in his very theatrical manner.

“Then I became interested in bodybuilding. I became a very popular sculptors’ model. Have you been to Baltimore? Well if you go, pay a visit to the Francis Scott Key monument on Eutaw Street. That is me in my prime there. I am also Cecil Calvert on St. Paul, and Lord Baltimore. They tell me I appear in more bronze and marble in more American cities than any man in history. On Wall Street I am the torso of George Washington, and at Harvard, Nathan Hale. Great patriots, all. And all of them courtesy of my body in its youthful prowess.”

While he was going on in that vein, I stole a quick glance over my shoulder. Two clean-shaven strangers were indeed standing off near a far post. One was a good head taller than the other, but each wore a thin-brimmed hat. They tried to look like they weren’t really interested in us at all, though clearly they were.

“No one I know,” I told Bushman when he finally stopped for a breath. He gave me a slight nod of understanding before going on.

“In the old days, a studio would take care of any problems that arose. Now everything is on one’s shoulders. One must pay attention to everything.” He sighed deeply. “It’s so sad to see what’s going on today. This used to be such a wonderful business, you know. Putting on shows for people who hardly make enough money to keep a stew on the stove. Somewhere the bosses have forgotten that. They learned there were fortunes to be made. And so did the cheap peddlers, the sleaze hustlers, the nepotists and the hopheads and the sex fiends. Get the point? Who is thinking of all the little people now?

“But I am not ready to give in,” he said, raising his chin dramatically. “I’m a fighter. When your mother names you Francis, you learn to fight at an early age. Well, thank you, my boy.”

“Mr. Bushman, may I ask you a favor? It’s Mrs. Addison. She keeps this book of autographs, and she’s your biggest fan, like I said. I told her if I got a chance —”

“An autograph? Certainly. Let me have it. And how would you like me to make it out?”

He was being so friendly all at once, I felt like I needed to talk while he scribbled his name. I told him a little about Mrs. Addison, and repeated her opinion that “Ben-Hur” was being financed back east by Jewish money because in the end it’s a Jew that wins the race.

Bushman finished signing his name before responding. “No, that is horse shit — pardon my language,” he said finally. “General Lew Wallace wrote his story to discredit such sentiments. The character I play, Messala, was steeped in the anti-Semitism of his day, and that existed in Rome long before the Crucifixion, believe me.

“General Wallace hoped to repudiate hatred and intolerance. The point is not that a Jew wins the race. It’s watching Messala get his comeuppance — that is what makes it such a thrill to readers. Hatred is self-defeating in the end. Please do tell that to your Mrs. Addison,” he said, slamming the book and placing it in my hand. Then he broke into a smile worthy of any hero’s statue, adding, “With my warmest regards.”

***

Who are those two spies, and how do they figure into “The Ben-Hur Murders”? Sorry, you’ll have to download the novel from Amazon.com.

You will find more background on the book at http://www.thebenhurmurders.com/, and on my fiction and me here at my author’s blog https://www.johnwharding.com/

Leave a Reply