The first great champion of narrative cinema, D.W. Griffith, brought his own potent blend of theatrics, social conscience and innovation to the developing art of motion pictures. Proudly he carried the banner of ancient poets and storytellers into an uncharted world and staked out new territory for future generations — all without uttering a single word.

Sadly, the studio where Griffith prepared himself for that noble expedition is lost to us today.

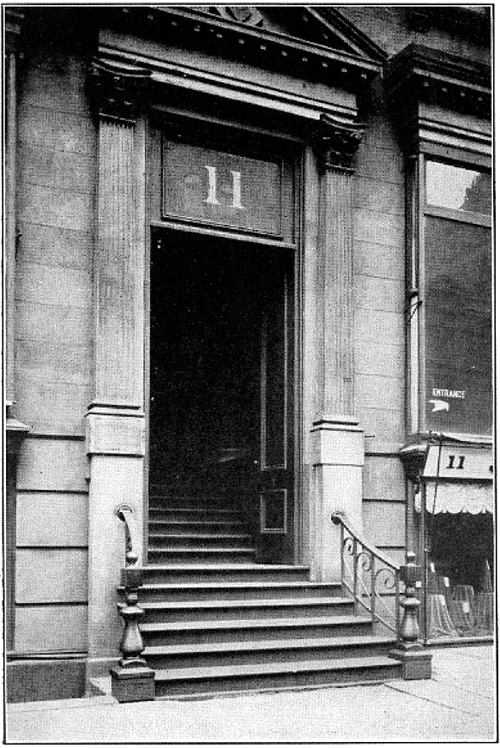

Beyond this door lay the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. When David Wark Griffith climbed the steps at 11 East 14th Street to enter this door for the first time in late 1907 he had just a first impression of how “flickers” were made — and not much desire to learn more.

He was a lanky, chisel-faced stage actor and a disappointed playwright. Since leaving his parents’ modest Kentucky home he had toured with many a hardscrabble theater troupe across the United States, appearing in both small roles and leading roles.

He had garnered a few good notices and been stranded in some pretty tough straits. Much of what he saw and experienced was bubbling up to the surface in his writing.

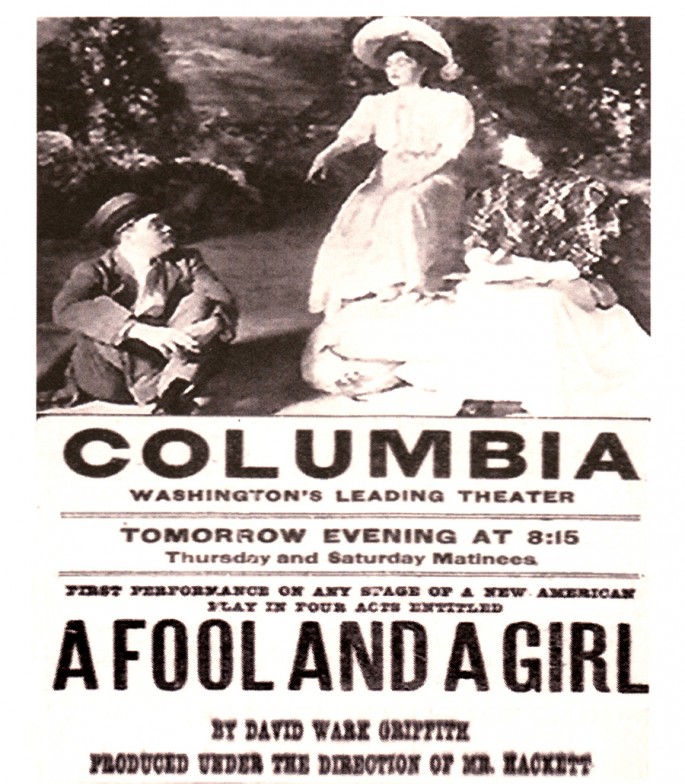

“A Fool and a Girl,” Griffith’s first produced play, closed forever in October of 1907 after a one-week run in Washington, D.C. Its self-pitying, melodramatic plot seemed dated to some, but at least one newspaper charged that it was too “modern” for impressionable youth. It focused on wastrel teens that patronized a West Coast drinking salon, speaking gutter slang and consuming alcoholic beverages in the middle of the day.

I recently read “A Fool and a Girl” at the Library of Congress, where it survives in manuscript form, probably typewritten by Griffith’s own actress-wife, Linda Arvidson. It provides quite a window on the psychology and the aesthetic sense of the future filmmaker.

In any case, it would not be the last time Griffith was blindsided by a negative reaction to what he intended less judgmentally as an unfortunate aspect of life.

Returning to New York City, David and Linda settled in a boarding house near Broadway. Like many a fellow Broadway actor “at liberty,” Griffith picked up some rent money by acting in a short movie at Edison’s Vitagraph Company.

Then in December he drifted over to American Mutoscope and Biograph Company on East 14th Street to see if they had any work.

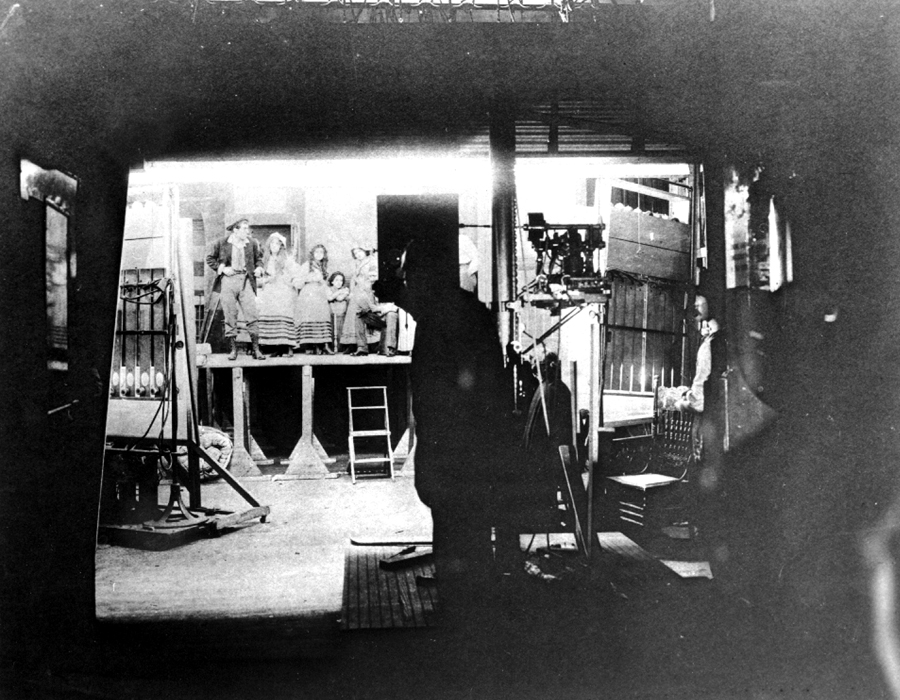

Through the first few months of 1908, Griffith and his wife both appeared in Biograph films and Griffith earned extra money providing ideas for scenarios. When a director’s job materialized there, he was deemed to have all the right talents to start making his own movies.

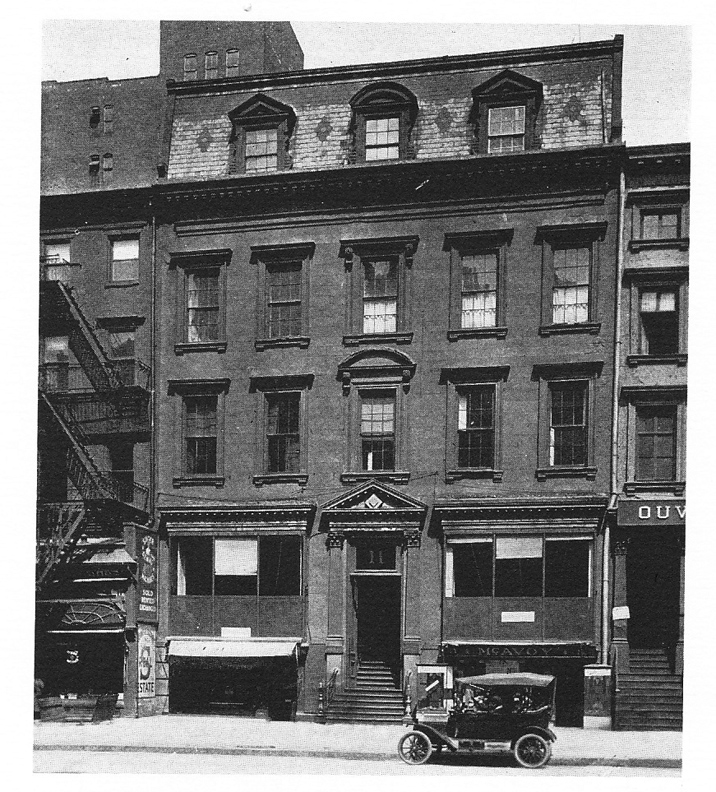

The American Mutoscope and Biograph Company was housed in a row of five-story brownstones that had once been the homes of New York’s well-to-do. After the Civil War, however, the brownstones began to be taken over by commercial enterprises and the wealthy residents migrated further uptown toward Central Park.

The 11 East 14th Street address changed hands and even served as a piano showroom for a time before becoming the headquarters and studio of American Biograph. Today, the address itself no longer exists. Just west of 2nd Avenue the old street numbers come to an end and the blocks are filled with modern high-rises. Nearby, however, one can still find blocks of brownstones that once stood as contemporaries of Biograph.

The neighborhood is just two blocks east of Union Square. Established in 1815 as a public commons for the city, it was named Union Square in 1832, and for decades its train station functioned as an entrance into New York City.

Starting in the 1870s, Union Square became the heart of the commercial theater district. Over time, the theaters gravitated toward cheaper real estate up town. But Union Square’s subway lines and railroad tracks made it convenient for Griffith and his actors to get to any film location in or out of the city.

RodNAzahar

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your

great post. Also, I have shared your web site in my social

networks!

Kim

Thank you for this post…I’m a lifelong film buff and lover of the silents especially, now pursing a Master’s degree in Film…am fascinated by the early days of film history in New York City, so hope to see more of what you’ve written. Thanks for sharing !

John Harding

Thanks, Kim. Glad to hear it.