Antisemitism and ethnic hatred were facts of life in General Lew C. Wallace’s 1880 novel “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.” They were also facts of life in Jazz Age Hollywood, when M-G-M turned the Wallace book into a classic silent film.

Antisemitism and ethnic hatred were facts of life in General Lew C. Wallace’s 1880 novel “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.” They were also facts of life in Jazz Age Hollywood, when M-G-M turned the Wallace book into a classic silent film.So when I set out to take readers behind-the-scenes of that 1925 production in “The Ben-Hur Murders,” I knew that antisemitism would have to play a part in it.

I have tremendous respect for the cinema pioneers and studio moguls who built “the Dream Factory.” But as much as I just wanted to tell a colorful story about movie stars and the thrilling chariot race that threatened to become an industry-wide scandal, I could not ignore that it all took place in a far less glamorous world.

Mussolini was already in power in Italy, Hitler was on the horizon in Germany, and thanks in part to 1915’s “The Birth of a Nation,” a re-invigorated Ku Klux Klan was parading for newsreel cameras down the wide avenues of Washington, D.C.

In Hollywood, most of the big movie studios were run by Jewish immigrants. But there were plenty of country clubs where they were still not allowed to become members. Many ordinary Americans were looking for someone to blame for the recent World War, the Bolshevik Revolution, the rapid urbanization of the country and such disturbing failures as the great 1921 depression, a preview of the 1929 Wall Street crash.

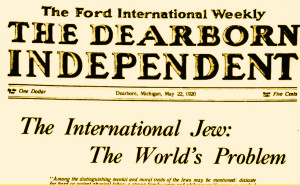

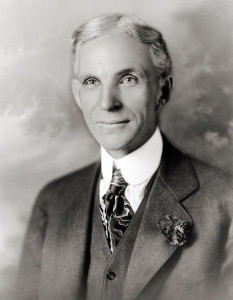

No less a powerhouse than automobile industrialist Henry Ford was spreading hateful tracts about an international Jewish banking conspiracy. His columns were published beginning in 1920 in The Dearborn Independent, Ford’s own newspaper, and were distributed throughout America via Ford auto showrooms. Much of what Ford wrote echoed European lies from an 1863 French political satire plagiarized and elaborated upon as “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.”

No less a powerhouse than automobile industrialist Henry Ford was spreading hateful tracts about an international Jewish banking conspiracy. His columns were published beginning in 1920 in The Dearborn Independent, Ford’s own newspaper, and were distributed throughout America via Ford auto showrooms. Much of what Ford wrote echoed European lies from an 1863 French political satire plagiarized and elaborated upon as “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.”

Miriam Cooper, the female star of “Birth of a Nation,” wrote in her memoir “The Dark Lady of the Silents” about acting in a 1921 film opposite “the most popular leading man of the day,” Conway Tearle:

“Playing a gentile with more than a trace of anti-Semitism, he was playing himself,” she recalled. “He went around making cracks about Jews. He alienated so many people … he phased himself out of pictures.”

It may not have been socially or professionally acceptable, but antisemitism in Hollywood was deeply entrenched.

It was always my plan for “The Ben-Hur Murders” to loosely parallel Wallace’s own tale of Judah Ben-Hur. Here I would present another era’s young prince, in exile from his Missouri home and family, forced to work at slave labor in Los Angeles, who finds himself unexpectedly presented with a chance at redemption. Once again it would all come to a head in a very public arena, and the hero’s salvation would again appear in the form of a perilous chariot race.

In my novel’s prologue, the naive hero, Grover, loses his day laborer job and is told about a position at M-G-M with its production of “Ben-Hur,” already the most expensive American movie in history:

Old Mrs. Addison was more than a landlady. She had once worked in the movies, sewing costumes and such for various studios in town. She told me about a new studio that was looking to hire what were known as “extras,” and she showed me the ad in one of her fan magazines.

“What do they pay?”

“A buck-fifty a day,” she said, “plus lunch, of course. This one might pay a little more. It’s got itself a budget. There’s big New York money behind this one …. Jewish money,” she added with a nod for punctuation.

I asked Mrs. Addison why a lot of Jewish businessmen would risk so much money on a movie about Christians. She started to laugh and then lapsed into a cigarette cough and a bout of hacking. Finally she fixed me in her watery eyes. “Why you think?” she said. “A Jew wins the race!”

Grover soon finds himself hired to help wrangle horses for one of the chariot teams. Later on, in the makeshift livery stables, he meets one of the stars of the movie, Francis X. Bushman, and asks him for his autograph for his landlady:

I told him a little about Mrs. Addison, and repeated her opinion that “Ben-Hur” was being produced back east with Jewish money because a Jew wins the race.

Bushman mulled this over as he signed his name. “No, that is pure horse shit — pardon my language,” he said finally. “General Lew Wallace wrote his book to discredit such anti-Semitism. The character I am playing, the Roman commander Messala, was steeped in the anti-Semitism of his own day, and it existed long before the Crucifixion. That’s very clear from what he says. Watching him get his comeuppance in the chariot race — that was General Wallace’s violent repudiation of all hatred as a way of life. That’s what makes it such a thrilling experience for those of us raised in homes with Judeo-Christian values. Tell that to your Mrs. Addison,” he said, slamming the book and placing it in my hand. Then he broke into a smile worthy of any hero’s statue, adding, “With my regards.”

Leave a Reply