“Whither goest thou?” asks the Latin title to one of world cinema’s earliest blockbusters, “Quo Vadis?” When it comes to the film studio that made “Quo Vadis?” back in 1912, however, the question becomes not where was it headed but where did it go?

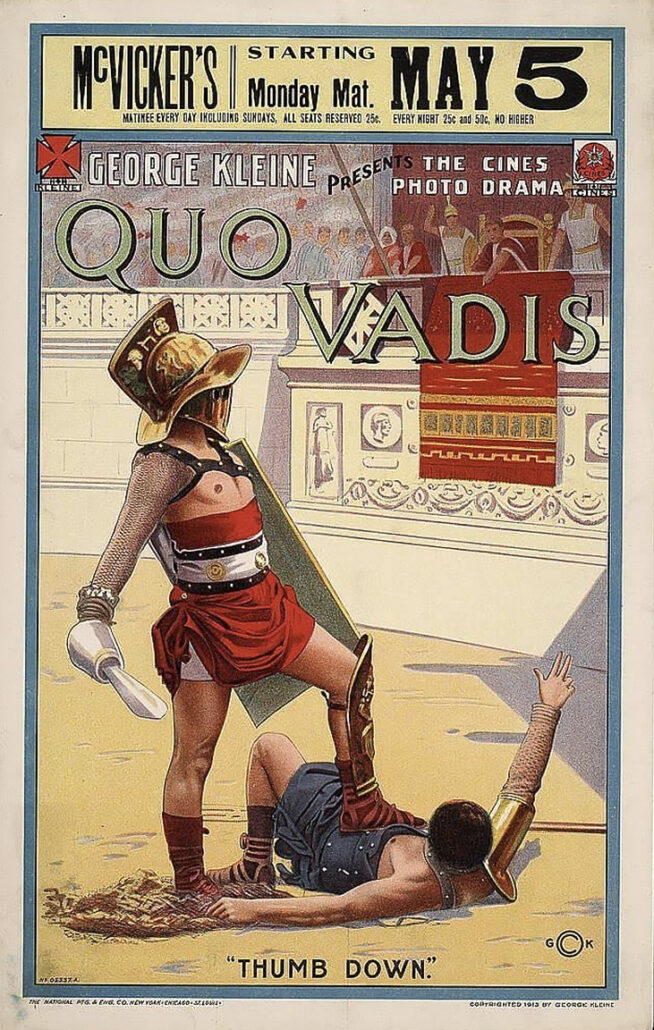

‘Quo Vadis?’

Between 1905 and 1956, the Societa Italiana Cines, commonly known as Cines (CHEE-ness), released 153 feature films. “Quo Vadis?” put it on the map, though it produced other international hits as well, including “Napoleone a Sant’Elena” (1911), “Marcantonio e Cleopatra” (1913), and “Cajus Julius Caesar” (1914). …

Then World War I came along and paralyzed Europe’s entire movie industry.

Cines might have remained a footnote in Italian film history except for the one movie it made in an unusual partnership with Hollywood. That movie was another religious epic, the silent “Ben-Hur.” Production in Rome on “Ben-Hur” began in 1923 with high hopes under the auspices of Goldwyn Pictures, and it ended in 1925 in humiliation and tragedy for the newly installed leadership at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Some believe MGM executives pulled the plug on “Ben-Hur” only a hair’s breadth ahead of being run out of the country by Benito Mussolini.

Three years ago I set out to write a chronicle of that tumultuous partnership in Rome. It was to be a sort of prequel to my 2015 novel “The Ben-Hur Murders,” which takes up the production months later in Culver City. I thought I knew much of the background of the story already, and continued to be fascinated by the era’s political upheavals during the dawn of Fascism.

Researching a book is the surest way to satisfy one’s curiosity. It’s also the quickest way to uncover the gaps in the historical record.

I could not find a single photo of the old Cines studio. The West Coast “Ben-Hur” holdings at the Margaret Herrick Library and in the USC Film and Television archives were of little help when it came to events in Italy. Public and private Italian resources were decimated by two world wars, and film historians there focused more on production budgets, distribution licenses and box office revenue than on the physical studio itself.

Much of what I learned about Cines during those “Ben-Hur” years came from a handful of references in published memoirs—and from what we now know it lacked.

The Perfect Studio

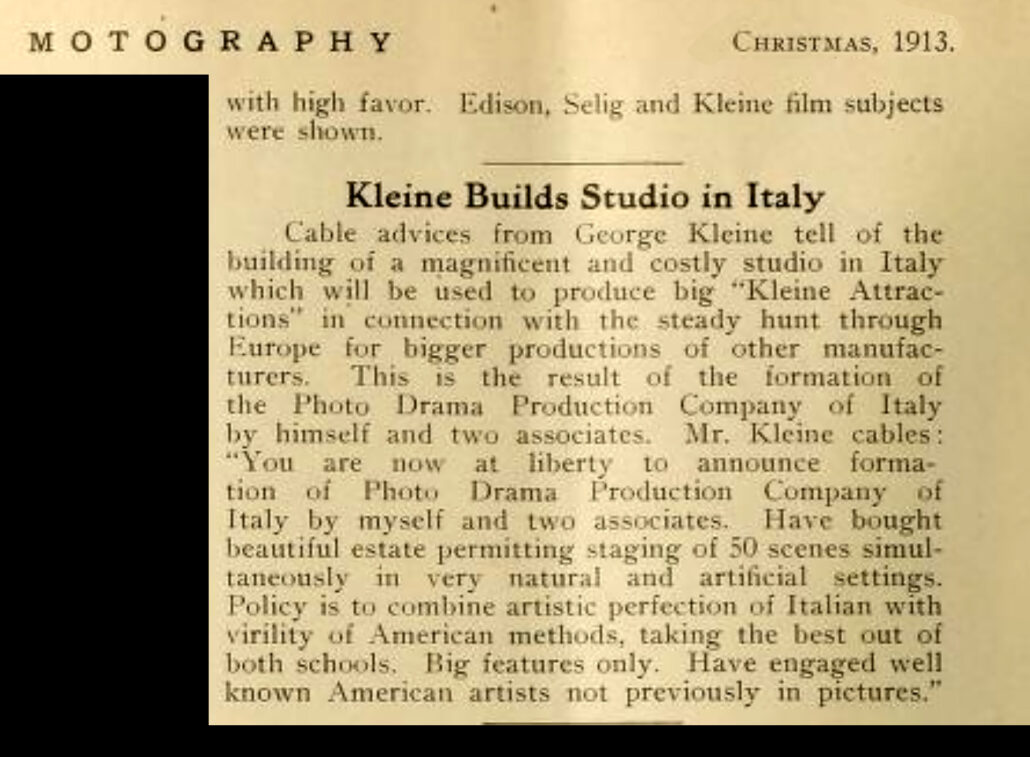

George Kleine was an American distributor who became the chief representative of Cines films in the United States. He was an ally of Thomas Edison in the patents wars and a co-founder of the Kalem Studio in Chicago (he was the “K” in the amalgam “K-L-M”).

While Kleine’s headquarters were in Chicago, he could always negotiate his licensing deals with Cines in its Manhattan offices. But he loved Europe and made frequent trips there. After visiting the Cines studios, the businessman saw an opportunity in opening his own movie factory in Italy. He found the ideal property at Grugliasco just outside Turin. Bringing aboard a couple of partners, he launched the Photo Drama Producing Co. at Grugliasco.

Kleine planned to populate his new studio with Italian labor, which could be had at around 25 cents a day, as opposed to the going rate in America of about $5 per day. With savings like that he could afford to hire American filmmaking talent and import “name” stars.

Kleine managed to keep his dream alive despite the outbreak of war and the limitations it placed on travel and resources in Europe. In 1916 he proudly published photos of the sprawling grounds at Grugliasco, which included glass-walled studios, carpentry shops, processing labs, foreign sets, “California” woods and even a small swan lake. It was clear that a key ingredient to any successful studio was the amount of land at its disposal.

George Kleine was always seen as a threat in the marketplace by U.S. film executives. Few tears were shed at the demise of his Grugliasco complex after the war. But when Goldwyn executives came to Italy scouting production headquarters for “Ben-Hur” in the next decade, they found that Cines met all the chief criteria.

Land Grabs

At its peak, when Cines released “Quo Vadis?,” Italy proclaimed filmmaking to be its “second industry.” There were reportedly some two hundred movie companies active at that time.

Movie studios in California were called “lots” because most of them grew up in vacant fields behind lumber yards and such. But real estate in Rome was never easy to come by, which is why ancient Romans waged war on their neighbors in the first place.

Cines occupied about four hectares of formerly Etruscan land—ten acres in all. It rested twenty kilometers northwest of the Eternal City outside Via Veio in a walled estate. Cines used its profits from “Quo Vadis?” to expand its boundaries.

Officially, Cines was managed by a “producing trust” known as L’Unione Cinematografia Italiana. In essense it was a monopoly run by a wheeler-dealer named Stefano Pittaluga. He didn’t care a whit about the art of cinema. Producing movies was just a way of guaranteeing a steady stream of new product for his own string of movie houses.

Historians argue that Goldwyn Studio chiefs chose Cines for its extra space. That was partly true. It certainly gave it an edge over rival companies like Ambrosio, Palatina, Itala and Pasquali. But Hollywood executives then were more or less the way they are today. For them Cines’ most notable asset was its proven track record. They wanted something they could point to if their decision to partner with the Italians turned out to be a fiasco.

The business leaders at Cines got the last laugh. A major stipulation in their contract obliged the “Ben-Hur” company to pay for all necessary renovations to bring Cines up to modern standards. Goldwyn’s hotshot financiers in New York should have spent more time looking into the state of their sister studio before signing on that dotted line.

“In reality,” reported the Hollywood trade papers later, “an entire studio is being built—from dressing rooms to wardrobe and carpenter shops.”

Tricks of the Trade

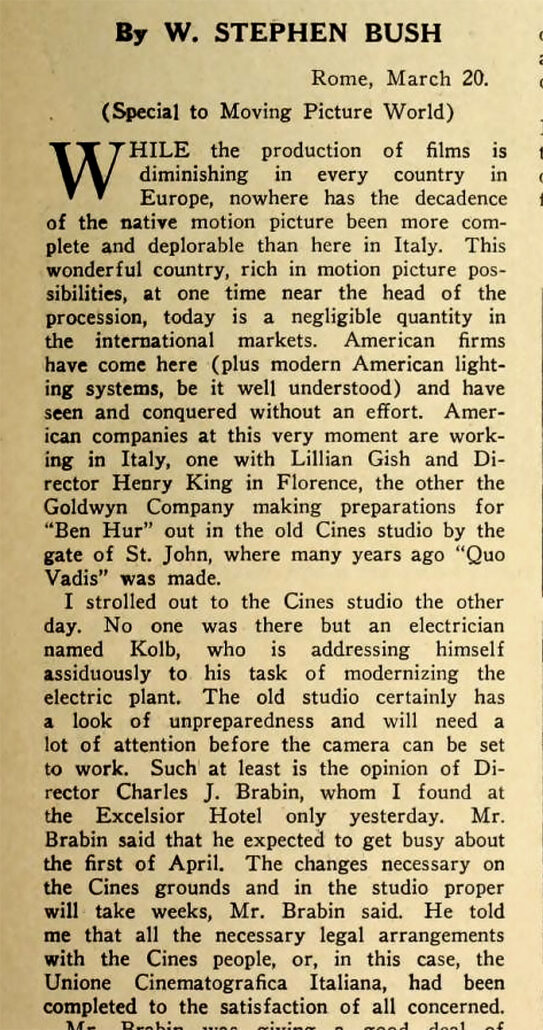

A reporter named W. Stephen Bush wrote of his experience at Cines for Moving Picture World in March 1924, when the majority of the production crew from the States arrived:

“I strolled out to the Cines studio the other day. No one was there but an electrician named Kolb, who was addressing himself assiduously to his task of modernizing the electric plant. The old studio certainly has a look of unpreparedness and will need a lot of attention before the cameras can be set to work.”

Bush quoted director Charles J. Brabin, who “expected to get busy about the first of April,” although “the changes necessary on the Cines grounds … will take weeks.”

That assessment turned out to be wildly optimistic. Cines had fallen into total disarray.

From studio records we know that in its first six months in Italy, Goldwyn paid for 125,000 tons of steel, masonry and lumber, all of it delivered to Cines. The country’s post-war economy had been at such a standstill that business leaders were eager to milk the visiting Americans.

Mussolini must have been pleased by all the sales tax and business fees he was reaping from the alliance with Hollywood. It meant he could afford to build the roads and stadiums he promised his people, all the while boasting to the world of the superiority of the Fascisti economy.

Crashing the Gate

In my novel “Cast Aside: With Bushman at the Unmaking of ‘Ben-Hur’ in Italy” I describe how the studio might have appeared to a visitor:

The old studio co-existed on uneven village roads in a warren of taverns, pharmacies and pensions, hidden behind thick stone walls covered in plaster and efflorescence. A secluded carriage road wound around back to a chained delivery gate and past rows of untamed bougainvillea hedges to a guarded private entrance.

At the height of the push to bring Cines up-to-date, the air inside those walls must have been heavy with the musky stench of damp cement and the pungent fumes of turpentine. Down hallways blew the orangey-sweet smell of fresh-cut timber and the chalky grit of sandblasted brick.

At the center of all this industry sat a squat, three-story villa with towering doors of dark wood pulled up at its front like a drawbridge. Inside were vaulted bedchambers and beamed libraries, all in the process of being gutted and remade into production offices and storage rooms.

Out a rear door lay a traditional Italian garden of flowering shrubs and murmuring fountains. Rock footpaths branched off toward a film lab for the processing and printing of negatives, and to costume shops and makeup departments, barbershops and canteens. An armory stocked with make-believe weapons sat next to a blacksmith’s foundry and an archery range. There was even a small fire department complete with firetrucks built on the frames of old circus wagons.

A large gymnasium waited off beyond the piazza to host sparring exhibitions and competitive boxing. Nearby was an infirmary with six beds and a full-time physician. The largest of the new structures was an indoor stage some 175 feet wide, and next to it was the employees’ cafeteria.

Extra storage was provided by temporary greenhouse structures erected along the outside perimeter. We know this today because late one night in January of 1925 one of those greenhouses was firebombed. Before the fire trucks could be mobilized the unit had burned to the ground, along with a dozen golden chariot cars and a collection of large wall tapestries and rugs.

That greenhouse fire was labeled an “accident,” which is suspect on its face. It followed a whole string of so-called “accidents,” from suspicious damages on sets to fatal mishaps during filming at the Circus Maximus. The most costly occurrence of all was the unplanned October sinking of MGM’s Roman warships in the harbor at Livorno.

In “Cast Aside,” these misfortunes are seen as conscious acts of political defiance intended to weaken Mussolini’s grip on the economy. If they were indeed acts of resistance, they would rank as the beginning of Europe’s anti-Fascist awakening and the first blows struck in what would soon be World War II.

In any case, the net effect of all the setbacks—willful or otherwise—was to speed along the exodus of Hollywood. MGM admitted its defeat and ordered its shell-shocked “Ben-Hur” veterans home to Culver City.

It would be over a decade before Mussolini brought all the resources of his government to bear on reviving the national film industry. He recognized the “usefulness” of film in building culture and channeling patriotic fervor. In 1937 he founded Cinecittà, and Cines was allowed to sink back into obscurity.

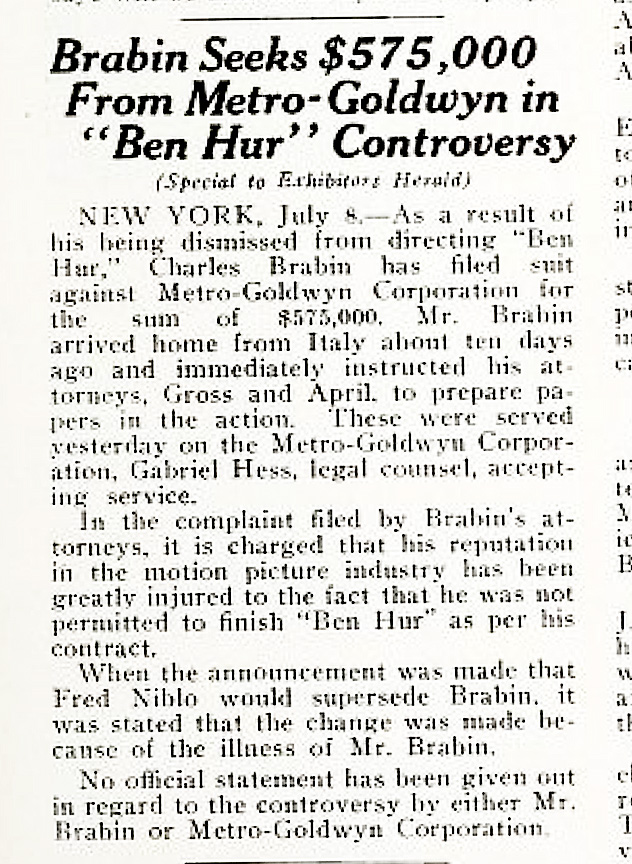

(Post-script: Charles Brabin dropped his lawsuit against MGM and was able to make twenty more films in Hollywood, including “The Mask of FuManchu.” But he is maligned to this day as the original “Ben-Hur” director who had to be fired due to his poor performance. In truth, the cards were stacked against him. There was not a director on Earth who could have made any headway on a project like “Ben-Hur” while also tackling the re-invention of an entire studio.)

(Post-post-script: Stefano Pittaluga assumed greater control over Cines after “Ben-Hur” withdrew. His marketing philosophy affected Italian film production throughout the 1920s. When the world transitioned to sound, Pittaluga navigated Cines toward making Italy’s first sound films, “Napoli Che Canta” and “La Canzone dell ‘Amore.” Pittaluga died of an unknown illness at age 47 in April, 1931.)

(C) 2022 by John W. Harding. Parts of this article are drawn from his novel “Cast Aside: With Bushman at the Unmaking of ‘Ben-Hur’ in Italy.”

Leave a Reply