Flooding from Hurricane Harvey in Texas this week sent me looking for an old friend who photographed the aftermath of the horrific Galveston hurricane of 1900.

The great G.W. “Billy” Bitzer was a cameraman at American Mutoscope and Biograph Company when he was asked to pack up his camera cases and tripod to go capture moving images of the cataclysm.

Billy is a player in my upcoming historical novel about the early moviemakers, and we have become quite close over these past few years of writing. I felt I could prevail upon him to give us his account of the experience.

He is usually a quiet man of few words. I did not expect him to address the subject at such length.

“I started in moving picture photography when a few progressive spirits were trying to utilize it in selling machinery — showing prospective customers outside the big city how some piece of machinery worked in action. It was a sales tool. The buyer would peer into a box through a lens and watch the postcard-like photos flip by. That was our Mutoscope.

“Later we learned how to throw our moving images up on a screen. A few ladies in New York fainted on the floor at Hammerstein’s when they saw the big Empire State Limited coming out at them. I was the one who turned the crank and got that footage. This was around 1896.

“The New York Central liked what we did and offered us courtesy-free passage anywhere we wished to go. They gave us special cars and engines so we could take pictures of the passing scenery. These were called ‘railroad scenics.’ I shot Union Pacific’s flagship outfit, the Overland Limited, which was a wood-burner still, with that funny, inverted funnel-shaped stack and the cow-catcher out front. We covered 30,000 miles on just one trip for Canadian Pacific once.

“This was all very exciting for a young man who grew up in an immigrant family in Boston. My father came from Germany and was a blacksmith by trade. He made fine leather harnesses and hoops for carriage wheels on a forge and anvil.

“I was a quiet boy, with two secret passions — one was for science and the other for magic. I wanted to know how everything worked. But I also loved showing people the impossible. Motion pictures appealed to both of those sides.

“In those days Biograph liked to scoop the competition with what was called ‘News Happenings.’ When the USS Maine was attacked in Havana Harbor, I was sent to Cuba to shoot footage of the wreck. I was back home already when war was declared. So they sent me back to make movies of the Spanish-American War.

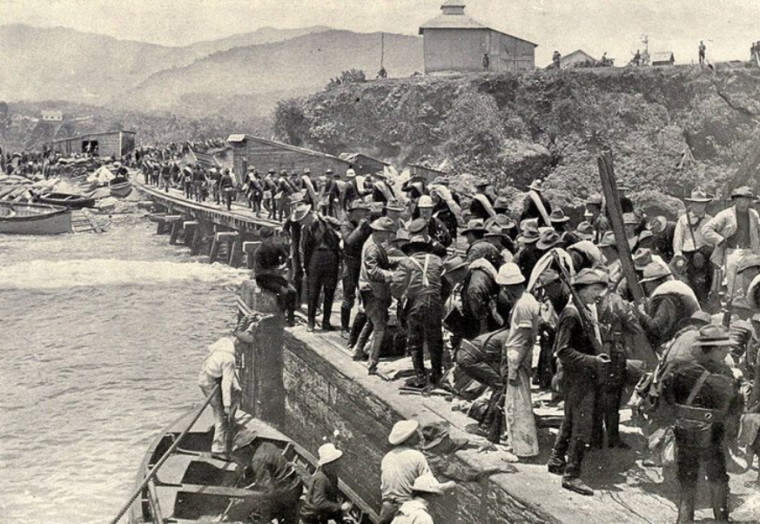

“I took shots of the troops landing from the Yale and the Harvard, two of the transport ships, and other shots along the beach there at Sibonney in Cuba.

I couldn’t advance with the troops, though, due to the scarcity of horses. They had shipped plenty of horses, all right, but they were all just pushed overboard at the harbor and most of them drowned because no one knew they had to hold up their heads in rough water.

“I was growing restless just filming the big battleships arriving. One morning a crewman shook me awake and told me my big boss was there. Out in the harbor the yacht Sylvia had anchored with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst aboard and a couple friends and a pair of pretty young ladies, who were sisters. Champagne and lively companionship did a lot to relieve the tensions of the war.

“You ever hear of Frederic Remington? He was a great American painter of the Old West. But when I knew him he was a war correspondent for Hearst’s New York Journal. He was ending his stay in Cuba so he gave me his horse. I was finally able to get to the battlefield for some proper war footage. I remember shooting the general and his staff crossing a stream on horseback. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders came galloping by us at one point.

“Unfortunately, I drank some local water and started to get very sick. My skin turned yellow and they thought I had yellow fever. It turned out I just had typhoid malaria, which is why I survived. But my weight went from 165 to 97 pounds.

“What did you want to hear about? Oh, yes, yes. You wanted to hear about Galveston.

“It was early September, 1900, when the hurricane broke along the Texas coast. For four hours the city was one black hell. Forty thousand people cowered in terror as dwellings went down like a house of cards.

“Biograph assigned me to cover it from the motion-picture angle. All I took with me was a suitcase containing raincoat and boots, and the new lighter portable Biograph camera and tripod. In Hoboken I caught the special relief train — just two Pullman sleepers and an express car. We traveled from Buffalo to St. Louis to Houston. The storm center at Texas City was as far as the train could take us. All bridges and tracks were washed out.

“The water was thick with the stinking remains of dogs, chickens, cows, horses and the bodies of human beings. As far as the eye could see there were massive piles of timber, scattered and torn.

“The stark, swollen bodies of women and children were lined up on the shores, waiting for burial. More bodies floated farther out like corkwood, but all would soon come drifting in. Funeral pyres were the only way to guarantee permanent disposal. The blazes gave off a strong light and deep shadows, all of it appearing as unreal as Dante’s Inferno.

“Next morning I was up early and on the job. No one seemed entirely sane. There was madness in the air. When the waves washed up bodies, they seemed alive, as their arms seemed to stretch out for help. It was so sad to see some tiny child, so doll-like, come floating up and spread out its arms.

“I shot pictures of this, but I doubted the public would be receptive to seeing it.”

Billy Bitzer remained with American Mutoscope and Biograph and was there in 1903 when the studio moved to new quarters at 11 East 14th Street — an address now famous in the history of motion pictures. In 1908 he was head cameraman when Lawrence Griffith arrived, some three years before the world would know him as film director D.W. Griffith.

What was life like for the pioneers of American movie making? Be sure to check back here for an update on the title and publisher of my new serio-comic novel about a pivotal time in the destiny of the studio known as Biograph.

© 2017 by John W. Harding

tom hammant

The devastation reminds me of what San Francisco looked like In the aftermath of the earthquake and fire just a few years later. Terrible.