“Art belongs to the young — born in the passions of loins and hearts, not in the abstractions of mature minds.”

– Terry Ramsaye in “A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925” (First Printing, 1926)

Anyone who believes that movie censorship began with the Hollywood “production code” clearly arrived in the middle of the picture. Let’s play that first reel again so that late-comers can catch up with the story.

Films of boxing matches were actually the first moving images to be legally outlawed, as boxing itself was against the law in the 19th century. But social behavior became the focus of censors with the 1896 short film “The Kiss,” produced for the Edison Vitagraph by no less a genius than Thomas A. Edison. Two beefy actors named May Irwin and John Rice were seen in this graphic recreation of the happy ending from their New York stage comedy “The Widow Jones.”

A kiss may be just a kiss in the words of “As Time Goes By,” but in 1896 it shocked park visitors in New Orleans who saw it projected at a Mardi Gras program of motion picture novelty “scenes.”

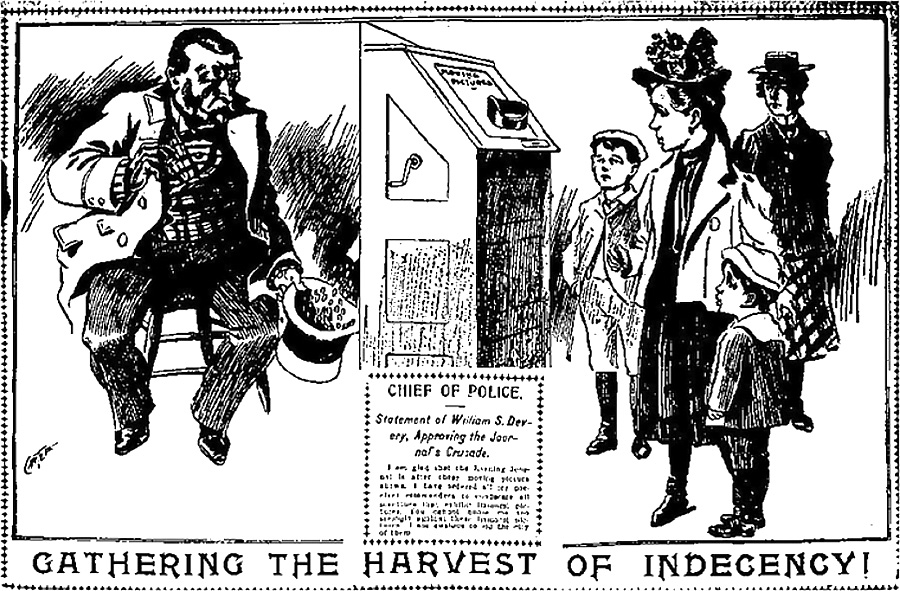

“Permit me to suggest that the too suggestive kissing scene be dropped,” ran an editorial next day in a New Orleans newspaper. “This may capture the fancy of the lascivious, but it is actually repulsive to the clean of mind.”

Moral censorship of motion pictures was born with the editor’s next sentence: “I am sure that the young ladies who resort to the park, and all careful parents, must prefer not to have this scene produced any more.”

It’s hard to think of such a respectable smooch as paving the way for the eventual arrival of “Deep Throat.” But as pioneering cameraman G.W. “Billy” Bitzer observed in his memoir, “It was really the puritanical American mind that made these pictures more pornographic than they were.”

Just as with “Deep Throat” eight decades later, the notoriety that met “The Kiss” sent everyone who was anyone rushing out to see it, mainly so they could say they saw it. And if they weren’t delighted with what they saw, they would never admit it, except perhaps to their clergymen.

For motion picture producers the search for thrills and titillation became the new Klondike gold rush. And the proper job description for any moral watchdog now included the duty to run around yapping at their heels.

That dynamic was set in concrete decades before Harold Lloyd’s famous specs were immortalized in the forecourt of Sid Graumann’s Chinese Theater. It would quickly lead to the first political skirmish in the war against motion pictures.

Remember the year 1908. That is the year the crackdown came in an action known among showbiz insiders as “The McClellan Christmas Eve Massacre.”

But wait. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. How could we leave so many juicy parts lying on the cutting room floor?

When Edison wasn’t signing off on drawing room sensuality or inventing incandescent bulbs, this so-called “Wizard of Menlo Park” was also exploiting the shock value of horror. In 1895’s “Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots,” audiences got to watch the ax fall and the poor queen’s head roll. (I’m sure the actress was proud of that roll.)

Shocking subjects like these were generally found in penny arcades thanks to “peep show” apparatuses like the Kinetoscope and the Mutoscope. The latter device was adopted by the Biograph Co., which migrated away from “news happenings” like coronations and hurricanes to “historical” re-enactments and its own forms of pandering.

The American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. had its first big commercial hit with a suggestive film of Little Egypt, the most popular dancer of the day. According to cameraman Billy Bitzer, it was followed by arcade favorites like “Serpentine Dancers,” “How Girls Go to Bed,” “How Girls Undress” and “The Birth of the Pearl,” featuring a woman in white tights and bare limbs posed in a giant oyster shell.

Biograph followed in Edison’s more macabre footprints with “An Execution By Hanging” in 1905. But by then the world wanted its motion pictures projected on a screen, like “The Kiss” and more recently Edwin Porter’s 1903 sensation, “The Great Train Robbery.”

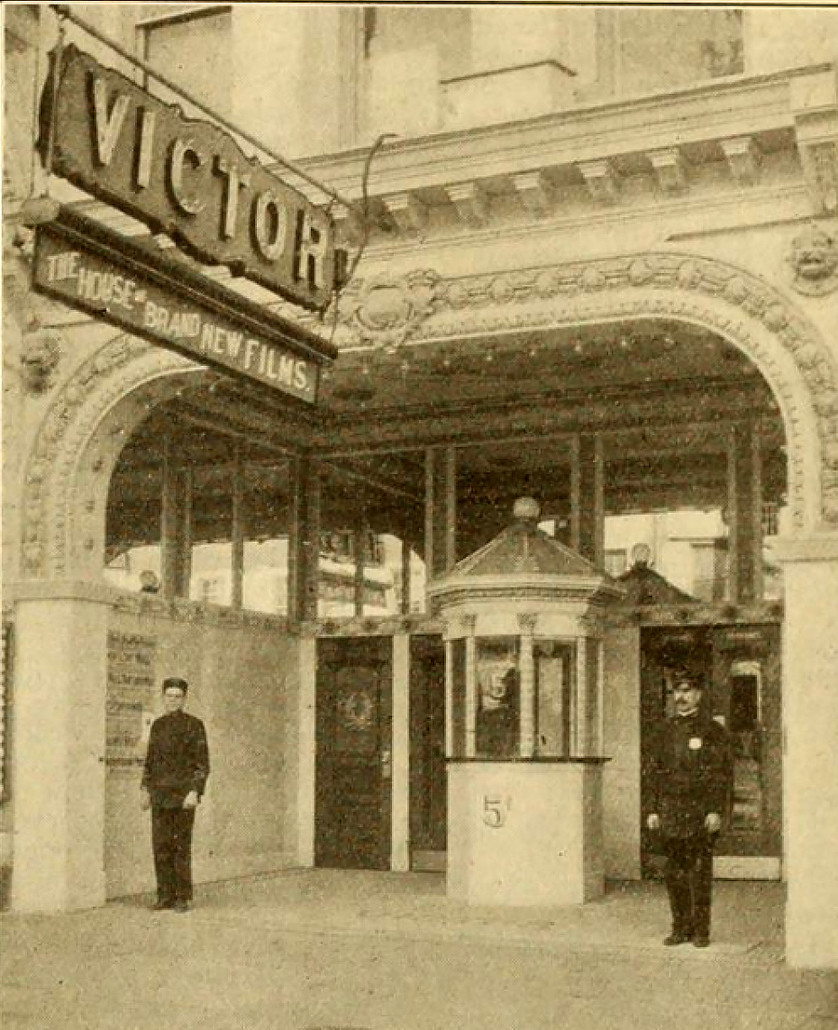

Across the nation sprang up hundreds and thousands of new “nickelodeon” theaters, thus named because they charged only 5 cents to get in. Often set up in abandoned shoe stores and other shops, the nickelodeons in New York were limited to 199 seats. Any more than that and they would fall into the “theater” bracket and be charged higher licensing fees.

But avoiding the theater label also meant they did not have to conform to the city’s business regulations nor pass safety inspections. A popular attraction at the neighborhood Bijou might find mobs paying to stand in the back or sit in the aisles.

Just as the popularity of “flickers” was spreading, this new form of “everyman’s theater” was bringing many of society’s worst manners to the table. The new American film industry seemed to be glamorizing crime, gun violence, death, sex and alcohol. It did not escape the notice of civic groups, clergymen and self-elected mental health experts.

The Philadelphia Telegram editorialized that many filmed entertainments “are the old dime novel in action, and infinitely more powerful for evil.” The mostly young audiences attracted to them might suffer “a permanent debasement of taste and a chronic impairment of moral judgment.”

America was not unique in this. Other countries were already at work setting up censorship boards to oversee motion pictures.

The Biograph Co. hired a respectable Southern stage actor in the hopes of raising the moral standards of its films. That new director would one day be known by the name of D.W. Griffith. Biograph’s owners must had a sinking feeling when they saw one of his earliest films — a celebration of notorious American “libertine” Edgar Allan Poe.

Griffith, however, was indeed leading Biograph away from its “peep show” roots with high-minded stories derived from literature and history. But change was not coming quickly enough for some. Just before the important holiday season of 1908, an affiliation of moral reformers and civic crusaders got the ear of New York City’s Democratic Mayor George B. McClellan Jr.

A coalition of such groups as the anti-saloon Temperance League, the Women’s Municipal League, the Public Education Association, the Federation of Churches (along with leading clergymen like Canon William Chase), and others persuaded McClellan that it was politically unwise to allow the motion picture industry to proceed unchallenged.

McClellan, ambitious son of the Union’s famous Civil War general, was quick to see it was not in his advantage to defend nickelodeons. Using “Sunday blue laws,” fire hazards and lack of proper inspections as cover, McClellan issued an emergency decree revoking the licenses of all 500 of the city’s nickelodeons. The holiday season was financially the worst possible time for all sectors of the film industry to be closed. Mayor McClellan took the heat by hastily beating it out of town.

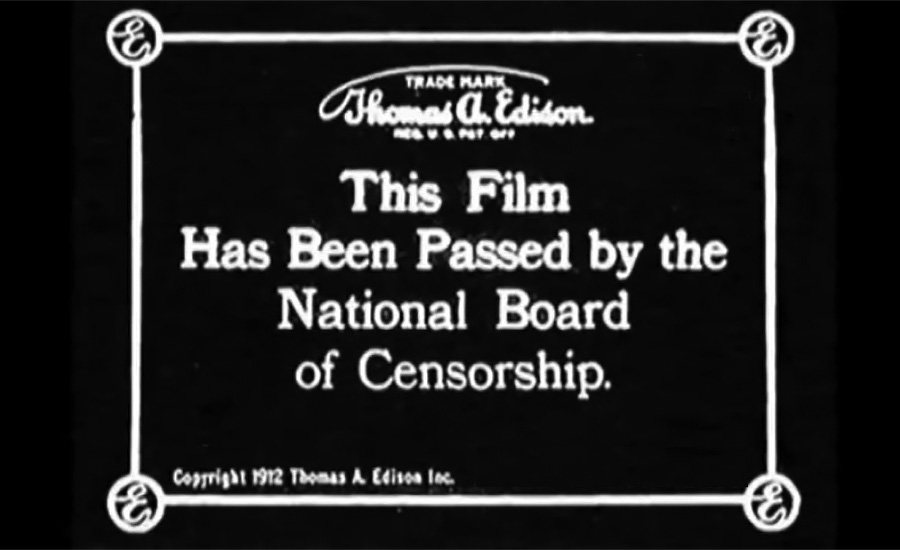

The 1908 “McClellan Massacre” did not stand up in court, thanks to an injunction won by the Edison Trust’s team of lawyers. But it sent a powerful message to the motion picture industry and led directly to the formation of the New York State Board of Censorship in early 1909. Soon afterward, the Motion Picture Patents Company promised rigorous self-regulation of the entire industry and founded the National Board of Censorhip. It promised that the new industry would regulate itself responsibly in future, and would not need government intervention in its business. It worked until it didn’t, and in time was the model for the Hays Office and the Production Code.

(My new historical novel, “The Designated Virgin” is a fictional treatment of this crucial era in the devlopment of American cinema. Look for it on Amazon and wherever fine books are available.)

© 2018 by John W. Harding

tom hammant

John, I am sure that your research only covers the censorship of “legitimate” films, etc., available for the general public of the time to see. The really “hard core” films that were probably being made and being shown at private “men’s clubs, ladies of the night houses, etc.” is not included as those would be hard to run down (the earliest one of this type that I know of was in 1915 in the U.S. but probably much earlier in Europe and South America). Interesting from a historical standpoint. Hey, human beings for eons have always been human beings even going back to the caveman era. LOL. 🙂

tom hammant

John, an additional comment to my above post. I am thinking that the major city police departments of that earlier era (e.g. New York City PD, etc.) would have raided some of those “private clubs,” etc., and seized the films/prints during those raids and that there may be records of them and dates of seizure at those police departments even today. Something you might want to check out, if interested. 🙂

John Harding

True, Tom Hammant. I am attempting to dramatize and illuminate the visible outlines of cinema history. There are others delving into the “secret” history of cinema. I will be really interested to hear your reaction to my story. Thanks for responding.

Valerie Lash

Very interesting stuff, John, especially since Baltimore has such a prominent history in film censorship! ~Valerie

John Harding

Thanks for the interesting reply, Val. Maryland as a whole does have quite a colorful background in the history of censorship. It was also one of the last states to hang onto the “blue laws.” In New York, Mayor McClellan had to respond to critics who pointed out that Sunday was the only day of the week that the new wave of immigrant Americans had some free time to experience leisure entertainment with their own families. He attempted to carve out some categories of businesses that could operate inside the blue laws, but it was an awkward bandaid fix for a bigger injustice. Thanks for reading!

tom hammant

John, I also remember when Maryland abolished the censor board. One of the Maryand House of Delegates mother headed the censor board at the time, I believe. I remember reading a few comments by her in which she indicated that she enjoyed the job as a grandmother keeping the muck out of the public movie screens. The article indicated that she was paid a good a salary as the Tsar of movie censorship in Maryland and her son fought hard in the Maryland House of Delegates to let her keep the job. I grew up in Chicago and I can also remember how hard Chicago/Illinois fought to keep their censorship in place and it really surprised me when I returned to the US from Europe in 1972 to see how much things had started to change. 🙂