Long before the first silent movie “vamp” and two decades before the public knew of Theda Bara, Olga Petrova, Pola Negri or Nita Naldi, Mrs. Patrick Campbell inspired the iconic myth of the female “vampire”—a sexual predator who sucks the élan vital from her willing but helpless male victims.

It was not until age 60 that Mrs. Patrick Campbell parlayed her fame and notoriety from a career on stage into notable film appearances in motion pictures like “The Dancers” (1930), “Riptide” (1934) and “Outcast Lady” (1934). Her final screen role as the pawnbroker in “Crime and Punishment” (1935) is hardly representative of the spell she cast in her prime.

Born in London in 1865, Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner turned the head of most everyone she met.

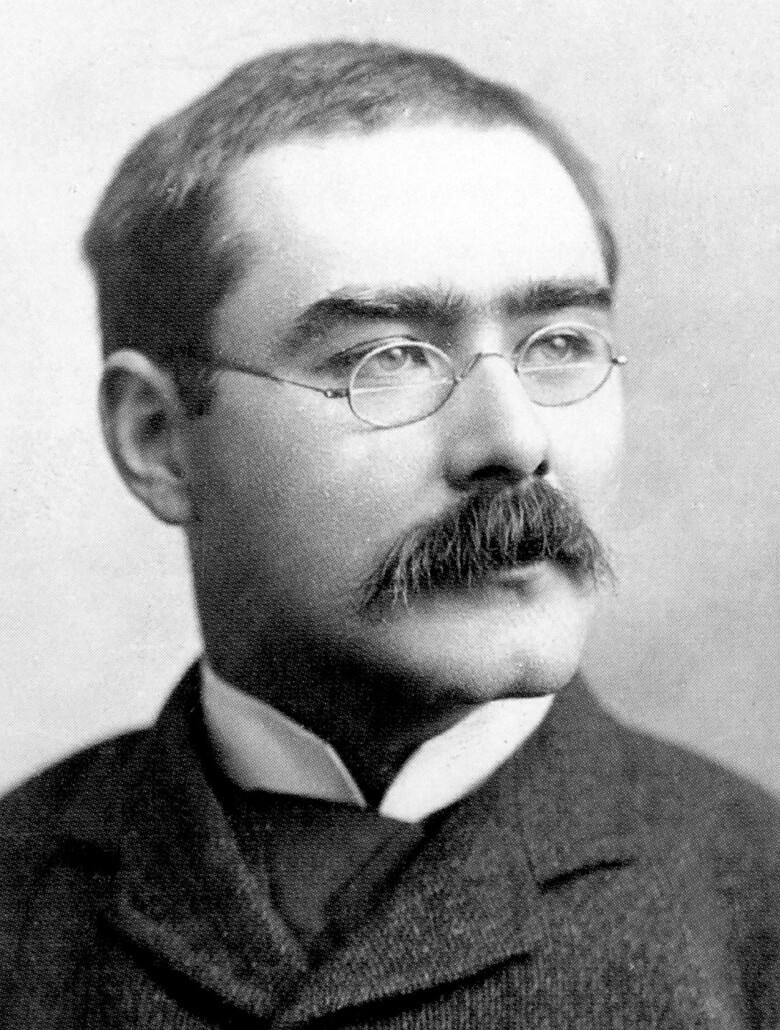

The list of her offstage dalliances and admirers reads like a “who’s who” of Victorian-era actors, poets and painters. It includes the three best-known dramatic writers of her time, Rudyard Kipling, J.M. Barrie, and George Bernard Shaw.

At 19 she found herself unmarried and pregnant, inveigling her handsome wastrel lover, Patrick Campbell, into eloping with her. Unsettled by what he had gotten himself into, Patrick escaped into his own globe-hopping adventures. He avoided the responsibility of fatherhood, though not the fate of getting himself killed in the Boer War.

By then his widow had found great acclaim on stage as Mrs. Patrick Campbell. She would be known by that stage name—or “Mrs. Pat” to intimates—for the rest of her life.

A fiery backstage romance with a well-known leading man of the day named Johnston Forbes-Robertson burned so hot that she had to stomp it out. Afterward the actor lost himself in the madness of alcoholism and an early end.

A friend of Forbes-Robertson happened to be a second-generation painter. Philip Burne-Jones was so shocked by the ruination of the actor’s life that in 1897 he produced the painting “The Vampire.” It shows a woman in her nightgown gloating over the unconscious body of a lover. The face and figure were clearly modeled on Mrs. Pat, though she never associated herself directly with it.

The painter’s own great-uncle (by marriage) happened to be famed British author Rudyard Kipling. He borrowed the name of his nephew’s painting for his own poem about the sad spectacle of male folly and the danger of fleshly hedonism. It begins:

“A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you or I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hank of hair,

(We called her the woman who did not care),

But the fool he called her his lady fair—

(Even as you or I!) …”

Thus the legend of the female seductress was coined and immortalized. In 1909 there followed a hit Broadway play, “A Fool There Was,” by Porter Emerson Browne. This is not to be confused with D.W. Griffith’s 1906 play, “A Fool and a Girl,” though Griffith admired Kipling’s poetry and may have intended his title as an homage. In any case, Griffith had just broken out of his own long and morally degrading love affair with an emotionally unstable actress. He might well have looked back on her as precisely the sort of “vampire” described by Kipling.

In 1915, Browne’s stage play was made into a film, also with the title “A Fool There Was.” Directed by Frank Powell and produced by William Fox, it introduced the world to actress Theda Bara playing a mysterious “woman of the vampire species,” according to a film intertitle. She preys upon a Wall Street lawyer on a trans-Atlantic cruise to England, dominating him physically and psychically with dialogue like, “Kiss me, my fool!” His destruction follows.

By the dawn of the Roaring’20s the notion of the female vampire had come full circle. In pop culture a “vamp” was softened somewhat, becoming far less lethal. It was attached to any femme fatale who causes men to turn their backs on respectable society and take a foxtrot on the wild side.

Like his father, Campbell’s son was also killed in war, in his case a shell fired in December 1917.

Mrs. Pat stole her last heart in 1914, the same year as her biggest stage triumph playing flowergirl Eliza Doolittle in Bernard Shaw’s “Pygmalion.” At the time, George Cornmwallis West was married to the mother of Winston Churchill, of all people. As Mrs. Pat later wrote in an oddly distanced voice, he was “seriously attracted to me.” As quickly as his divorce decree was granted, the two were married.

A best-selling volume of the letters between Mrs. Pat and Bernard Shaw was published posthumously in 1952. As for the world’s first “vampire”: Mrs. Patrick Campbell contracted pneumonia at age 75 and turned her final head in France in April, 1940.

(Fans of reality-based fiction and the history of filmmaking might enjoy my latest novel, “The Designated Virgin.” It is a rare visit to the Biograph Co. in 1909, where a mix of real and fictional characters battles the first wave of film censorship in the United States. The novel is published by Pulp Hero Press and is available at Amazon and other book sellers.)

(c) 2020 John W. Harding

Leave a Reply