When Lew C. Wallace was writing “Ben-Hur,” he knew that a thrilling Roman chariot race would give his novel a socko finish. But no lives were at risk until 50 years later when MGM actually staged that race for its 1925 epic film.

MGM already knew from past experience what could go wrong. More than 12 months earlier it had attempted to shoot the race on a location outside of Rome.

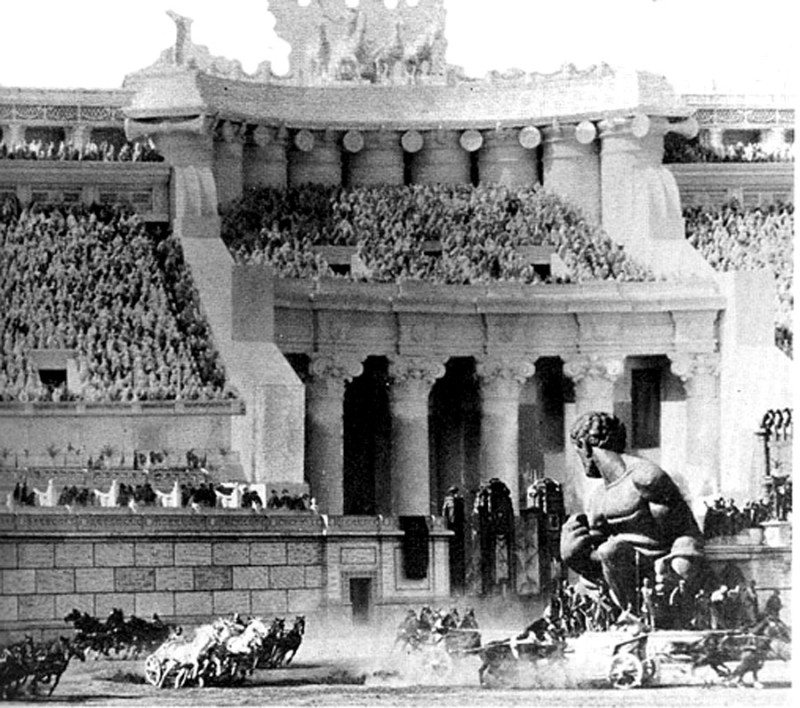

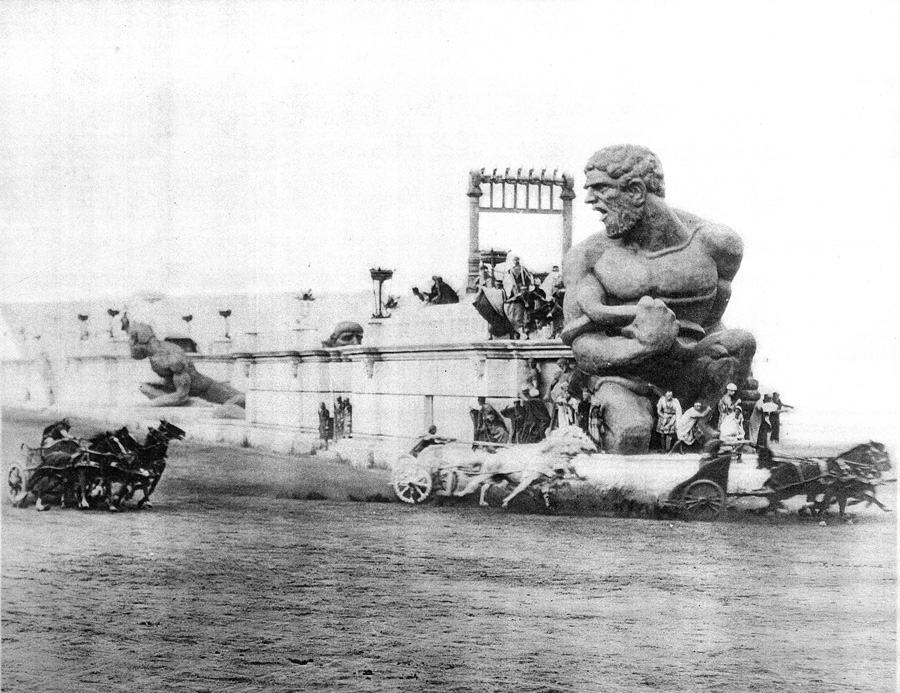

Few animals are more powerful or less predictable than a horse, and this sequence required 48 of them — four chained to each chariot. According to Wallace, there had to be 12 chariot cars, each representing a different region of the Roman Empire. Together they amounted to thousands of pounds of metal and lumber, all of it careening around a track of gravel and sand on flimsy wooden wheels at speeds upwards of 40 miles an hour.

In Italy, several mishaps caused long delays, so before the sun was lost the production company rushed to get all the cars into position to run the race for the cameras.

The second lap around the track, two chariots collided and overturned, dragging the horses headfirst into the gravel and causing a huge pileup. One stunt driver was killed outright and several others suffered serious injuries.

Over a dozen horses were also badly injured, many of them needing to be shot where they had fallen in order to get the chains untangled.

Silent film star Francis X. Bushman had signed on to play the Roman villain, Messala, hoping it would relaunch his lagging career. A physical fitness buff, Bushman had learned how to handle a chariot team and prided himself on doing his own driving until he realized how dangerous it was.

He witnessed the accident in Italy and described what happened there at various times over his next four decades, often inflating the account to include “dozens of stunt men and hundreds of horses.”

On October 17, 1925, MGM was ready to try again. This time the location was in Culver City, inside a fabulous new replica of Antioch’s Circus Maximus.

My novel “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games’ “ loosely mirrors the Lew Wallace novel, though here the entire action is set on that one day in Culver City.

As I did my background research on the Hollywood filming, I wrestled with a central question: How could so many smart and sophisticated artists — people like Bushman and Irving Thalberg, Fred Niblo, Ramon Novarro, Cedric Gibbons, June Mathis and scores of others — justify the dangers in the mere pursuit of show business glory?

Did they not recognize the potential sacrifice of horses and stunt men in the name of public entertainment? Did they not see themselves as engaged in a brutal throwback to pagan times, corrupted by the same lust for power that drove their Roman counterparts?

Two of the central characters in “The Ben-Hur Murders” do confront these questions, and the paths they choose to placate their consciences underscore the resolution of my novel’s themes.

But to understand the mind set of the time, one must look see it in historical context.

President Wilson may or may not have said that watching “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915 was like seeing “history written in lightning.” But many of his fellow world leaders certainly recognized the new power of motion pictures.

Josef Stalin seized on the art of film for its propaganda potential. And American inventor Thomas A. Edison believed it could even replace textbooks as a teaching tool. Storytellers around the world gave up the campfires of their ancestors for some of that new form of lightning.

Mistakes happened along the way, and many a sacrifice was made that might appear foolish to us now. The modern impulse is to look back and criticize or condemn those who came before us — as if we would have done everything differently and better than they did. But how can we know what we would have done unless we stood on their turf and shared their dreams?

Some of the new Hollywood moguls and megalomaniacs looked upon their endeavors as the equivalent of public road projects or massive dam constructions — well worth the risk to life and limb by the chosen few employed to work on them.

If a few horses died in the process, it was not that people did not value the lives of horses. Horses also died in rodeo gags and in leisure-time riding spills each and every day. And if the lives of a few stunt cowboys were lost along the way, it wasn’t that anyone saw human life as expendable. In those hard-luck times, hardly a week passed when a human being didn’t slip from a tightrope stretched over Niagara Falls, or freeze to death scaling Mount Everest, or drown while trying to free himself from an underwater safe in pursuit of headlines.

Today, all of that seems well beyond the pale of civilized entertainment. But when it came to conquering the unknown and astonishing the world, who could have said back then what the limits were?

It’s hard to blame MGM for what happened on October 17, 1925. It was the studio chiefs’ goal to create an astonishing spectacle that would satisfy a worldwide hunger. In the case of “Ben-Hur,” there was also its testimonial for universal peace and brotherhood to deliver.

If plans went awry or a chariot car design presented an unexpected hazard, the oversight was quickly addressed. Unions rose up to fight for workers’ rights and safety, and the public itself began to demand laws and societies to put a stop to wanton animal abuse on movie sets.

Both the art of film and the business of making movies had to go through an evolutionary process.

Fred Niblo’s “Ben-Hur” is still one hell of a picture, and it will be shown and marveled at and talked about until the day comes when people no longer need inspirational stories about the human will to grow and mend and plot its escape from the galley hold of life’s slave ships.

For all the pain and heartache it caused, “Ben-Hur” has surely brought joy and inspiration to millions of viewers across the decades. That’s a redemption of sorts for any human being, don’t you think, and a legacy any one of us might be proud to leave behind?

(c) 2015 John W. Harding

“The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games’” is available at Amazon.com as a paperback and Kindle download, and exclusively in hardcover at Lulu Press.

John Harding

Vraiment? Merci beaucoup. John