In 1925, Joseph M. Newman walked wide-eyed onto the most important movie set in Hollywood history. The 16-year-old newcomer from Utah had been hired as an office boy by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. But on that Saturday morning of October 17 he reported to a dirt lot in Culver City, where MGM would shoot the climactic chariot race for “Ben-Hur.”

“I worked on the chariot race as an office boy,” he told an interviewer late in his life. With a wry but characteristic humility, he added, “I gave out lunches.”

Joseph Newman, who died in 2006, had a colorful career in Hollywood, going from production assistant to Ernst Lubitsch and George Cukor, to director of “B” movies. He is credited with directing at least one genuine hit, the 1955 sci-fi thriller “This Island Earth.”

Yet, as an elderly man, it was that Saturday in 1925 that most animated his memories of “the dream factory.”

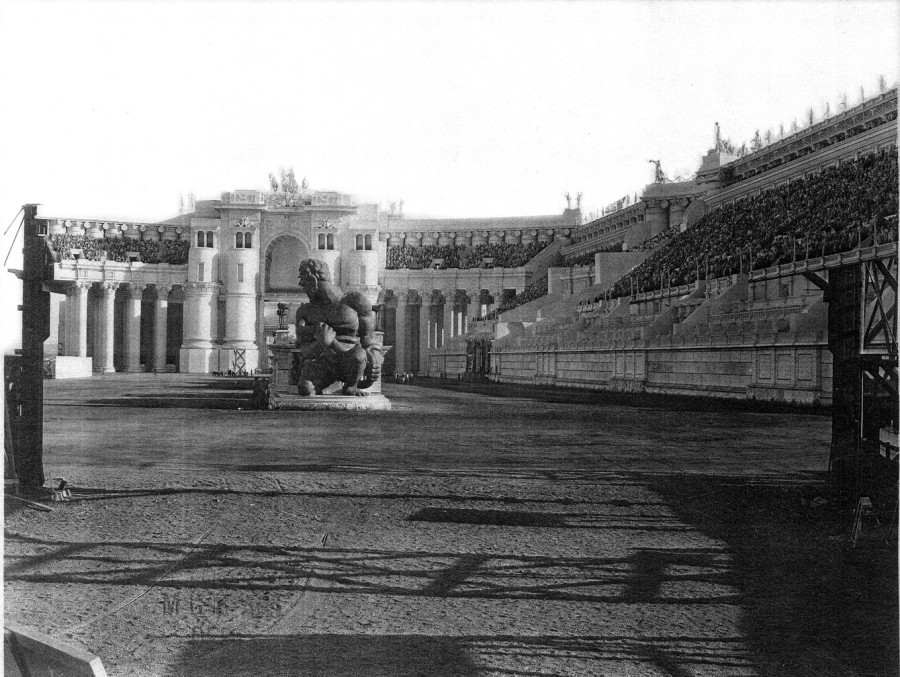

The movie set was an elegantly designed reconstruction of Rome’s Circus Maximus coliseum at Antioch.

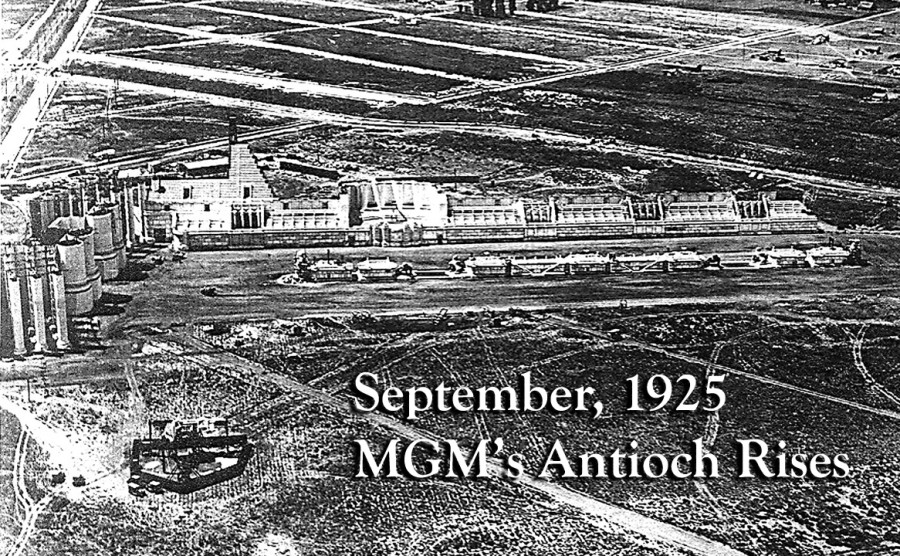

“You know where it was?” asked Newman. “It was where La Cienega runs into Venice Boulevard. It was just where that triangle would be today. Of course, it wasn’t La Cienega in those days. And there was no Venice Boulevard through there.”

“We had to come down Washington Boulevard. There was an old dirt road, and the studio leased that property and built the Circus Maximus there. They did the whole chariot race right there.”

This was actually the second Antioch coliseum built by MGM for its production of “Ben-Hur.” To protect its $600,000 investment in Lew C. Wallace’s best-selling novel, the new studio had hoped to shoot it on an epic scale in Italy. But after 16 months of labor problems and production shutdowns, Louis B. Mayer cut his losses and ordered the company home.

All of the costly plaster molds of palace cornices and imperial eagles used to recreate historic Antioch outside of Rome were packed in crates for the Atlantic crossing. But when studio accountants calculated the high import duties they would have to pay just to get them on the docks in the United States, MGM executives decided it was cheaper to dump them all at sea and pay designers and plasterers to start over from scratch.

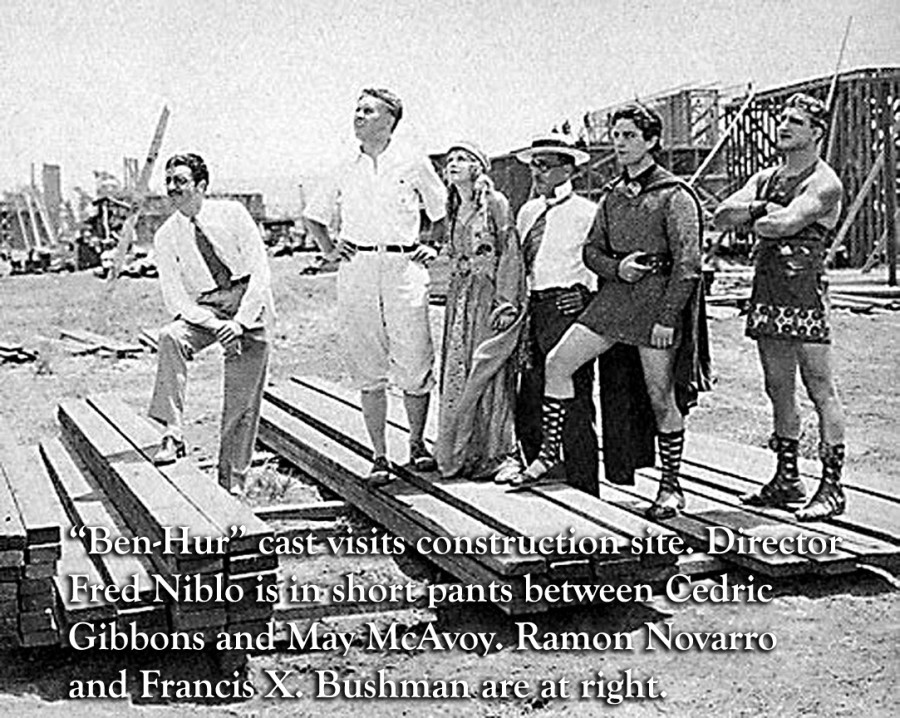

Mayer turned over the whole project to his hand-picked production executive, frail but remarkable “Boy Wonder” Irving G. Thalberg. Thalberg ordered up a new cast and crew, and throughout the summer of 1925, MGM built a new replica of the Antioch Coliseum at a cost of $205,000. It rested on several hundred acres of land in Culver City leased from the Marblehead Land Company.

Joseph Newman estimated that he passed out lunches to some 3,000 people who came to watch the filming of the big race. Not all of them were extras. Thalberg had mailed out printed invitations well in advance to all the industry elites, MGM employees and actors, and many top L.A. public officials, from the mayor to his police and fire chiefs.

Representatives of the press wrangled their way in, as did fan club presidents and legal teams. MGM’s chief executives and their wives were issued period costumes, and before the shooting of the main race, Thalberg and Mayer treated onlookers to a magnificent parade.

From the beginning, MGM always did everything with flair. The intention here was to dwarf all expectations. The parade itself, however, has been forgotten in the glamour, the excitement, and the horror of the race that followed.

Taking a cue from the 1925 silent film’s own triumphant “entry into Rome” sequence, I tried to imagine what the parade might have been like. What follows are highlights of the description from my fictional take on events of that day, “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games.'”

A cacophony of trumpet blasts rang out from the north end of the track. There a half-dozen men in Roman robes stood in a line with long, thin horns pressed to their lips. Beyond them was the archway leading to the stables, and beyond it could be seen an assembled throng waiting in formation.

Then a man in the stands waved a yellow banner and was answered by another flag to the south. A new blast of trumpets ripped the air, followed by the rattling gargle of drums. Suddenly the north gate began to hemorrhage marchers. Every idle horseman and would-be starlet in Hollywood seemed to have moved heaven and earth to be part of this parade.

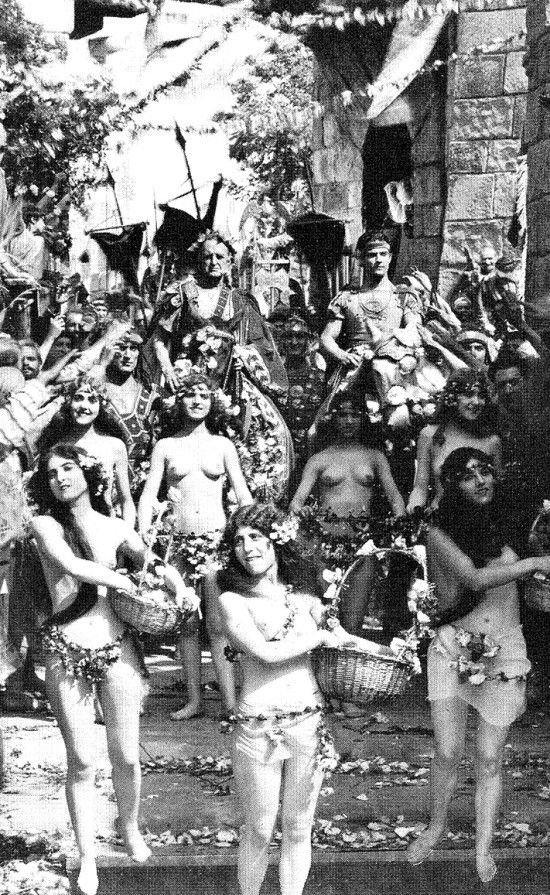

First came two streams of runners dressed like Olympics torchbearers, followed by a platoon of drummers and banner-wavers. After them appeared a trainer with a lion on a leash. It was Leo, the MGM mascot. Next came a prancing bevy of topless young girls, wearing only flowered necklaces and short skirts, split up to the waist on one side.

As they came strutting and frolicking down the route, they scattered rose petals in the air from earthen platters. Behind them marched a squadron of gold and maroon centurions, clanking along in their shiny breastplates and helmets, followed by mounted squadrons of Roman cavalry, armored mainly in woven-leather straps.

Just then Ramón Novarro emerged from the archway in his chariot behind his white stallions. The sight again set off a round of squeals and cheers in the stands. Then came Francis X. Bushman, glowering grandly across the backs of his four black Arabian racers. I don’t know if it was planned as a comment or not, but Bushman was closely followed by a rodeo clown pulling a rickshaw with a midget in the back. That got a big laugh.

There came an elephant, and some camels, and a man with a bear, and then an early Model-T careened into view on its skinny spoked tires. It was one of those boxy numbers with the extending fenders on both sides attached to wide running boards. Piled all over it and holding tight to the front headlamps were about a dozen Keystone Kops in their trademark mustaches and thimble-shaped caps.

Next, the teams entered in a single-file line of chariots. Each charioteer was dressed in native ceremonial garb with head gear appropriate to a region of the empire. The twelve competitors represented the twelve major provinces of the Roman republic. It was the first time I had seen all the chariots together and in motion, and they appeared like a toddler’s giant pull-toy — a string of Easter-egg colors gliding amid spinning golden wheels and gently pumping horse heads on a knitted cushion of leather and fur. Surely I was not the only witness there to enjoy a sudden wave of goose flesh.

As the parade passed in front of the stands and headed toward the stately Gate of Triumph, the pandemonium reached a fever pitch.

Following the charioteers and another marching platoon and more mounted centurions, out stumbled a lone figure in ragged robes and wearing a crown of thorns. His arms were tied to an oversized wooden crossbeam, which he carried like a yoke as a small band of Roman soldiers taunted him and poked at him with spears.

Yes, it was clearly meant to be Jesus on His final walk to Calvary. Some in the crowd must have found it vulgar and tasteless after all the hoopla and dancing girls that had come before it. The crowd grew hushed as history’s most beloved martyr passed before them. Then someone at the front of the stands recognized him as a washed-up cowboy actor named “Lariat” McCoy who had fallen on hard times. When old Lariat heard his screen name called out, followed by a smattering of applause, he couldn’t keep the smile from his face. I think he may have even given a small dip of gratitude to his fans with the end of his crossbeam.

It was as if Lariat forgot for a moment what he was doing and who he was supposed to be. Maybe he even started to believe he could be someone of importance in that town again.

(Excerpted from “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games’ ” by John W. Harding.)

(c) 2015 John W. Harding

Leave a Reply