I’ve always loved historical fiction. Historical fiction takes us as close as we can get to the people who actually lived through past events. Historians can’t do that; in fact, it’s not their job to do that.

But within the framework of recorded fact, the novelist can let his imagination roam freely and draw us into an experience of the past.

I loved reading Kenneth Roberts in high school. His “Oliver Wiswell” and “Northwest Passage” were far more alive to me than anything in my American history texts.

In “The Egyptian,” Mika Waltari made Egypt in the time of the pharaohs seem more immediate than the evening news. And the narrator not only knew how to perform brain surgery before scalpels and anesthesia, he displayed a universal weakness for one beautiful woman who led him to sacrifice everything, even his parents’ ticket to eternity, for one more night of bliss.

Dramatic crisis, psychological crossroads, human eroticism, page-turning suspense — these are instruments that the historical novelist has that the historian does not.

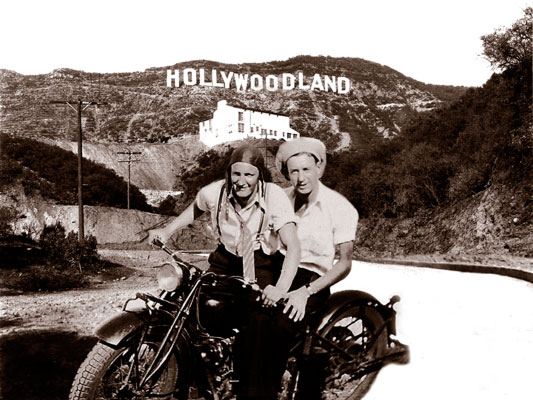

The photo above is my favorite photo of my father. He’s seated in the back wearing the hat in a funny way. He was born in Kansas, but his family moved to Los Angeles when he was still in grade school. That Hollywoodland sign was built in 1923 to advertise a new real estate development. But the photo was taken a little later, when my dad was 18. He probably didn’t have a driver’s license yet. He certainly didn’t have a motorcycle. But he did have a friend with one.

My dad had all sorts of stories about growing up around Hollywood. His tales of his first job digging ditches and of seeing movies being made became part of my own background. He used to love telling us about watching extras play soldiers in a movie. They would march in front of the camera, then run around behind it and get back in line to march by again. Hollywood’s “games” were never a secret in our house. I grew up reading all about the history of early movie-making.

A few decades later I went to high school not far from that same sign — it just said “Hollywood” then, and it was in need of repair. Growing up in Southern California in the psychedelic ’60s should have been distraction enough for anyone, don’t you think? But I was also by nature prone to distraction. My mind would wander in class. I was always looking for the drama of the Bigger Picture.

For me, one teacher who stood out from all the others at Lakewood High was Mr. Daniels. Mr. Daniels taught U.S. history the way it ought to be taught. He must have spent all his leisure time reading biographies and pouring over articles about the unknown bystanders to history. Mr. Daniels specialized in stories about the people whose lives were shaped by the big historical events we were studying.

No one who listened to his stories was likely to forget the facts and the real lessons of history. Mr. Daniels made it easy even for me to stay focused.

And that led me to the discovery of one of the great paradoxes of art — or maybe it’s not a paradox at all: The more focus you bring to the smallest detail, the clearer the Bigger Picture becomes.

At UCLA I was an English major, even though I didn’t really want to teach. I had written a play, produced by a community theater, and I knew I had a gift for expression and drama. So all of my electives were in theater and the history of motion pictures — two more ways for me to come to grips with the Bigger Picture.

Flash forward a few decades. I had found a good way for me to make a living — writing on theater and film for newspapers. I had good editing skills and was made the arts editor at Patuxent Publishing in Columbia, Maryland. All the time I was writing my own fiction as well. But nothing clicked for me until one day I read a short account of what happened during the filming of the great “Ben-Hur” chariot race in 1925. it seemed to contain all the essentials of a thrilling story.

MGM was the new kid in town, and this one famous sequence from the novel was either going to make the studio or break it. The execs hired a lot of stunt men and guys to help wrangle the 48 horses and 12 chariot cars — guys like my father, and old rodeo cowboys, and World War I veterans desperate for work. And they filled their replica of a Roman coliseum with invited guests and movie stars.

But when the race footage needed more excitement, the studio offered a purse of gold to the winning team, and it ran the race one time for real.

Suddenly I knew what I wanted to write about. It was Hollywood’s first reality show! But it was also more cruel than that, more dangerous — as arrogant in its way as the Circus Maximus games of ancient Rome. Could I capture that period and bring it all to life with just words?

I remembered my dad, playing hookey from school and joyriding around Hollywood with his buddy. That was the the spirit I wanted to capture. That’s what I wanted my historical novel of Hollywood to be about: Not some fan magazine fantasy piece but the Bigger Picture.

I didn’t turn the corner on shaping the material until I realized that there were two distinct perspectives on the events of that day. There was the view on the ground by the stunt men and studio roustabouts fighting for their lives. And there was the view from the V.I.P. stalls, where fortunes and careers were no less on the chopping block.

Add in the influence of the Jazz Age — Prohibition and bootleggers, labor union strife, the dawning of equal rights, the rapidly evolving technology that was taking silent film to sound, and my historical novel was ready to step out and meet the world.

Read about the exciting events of that day in my reality-based novel, “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games.'” It is available at Amazon.com as a paperback and Kindle download, and exclusively in hardcover from Lulu Press.

(c) 2015 John W. Harding

Chelsia

Wow! Talk about a posting knonikcg my socks off!