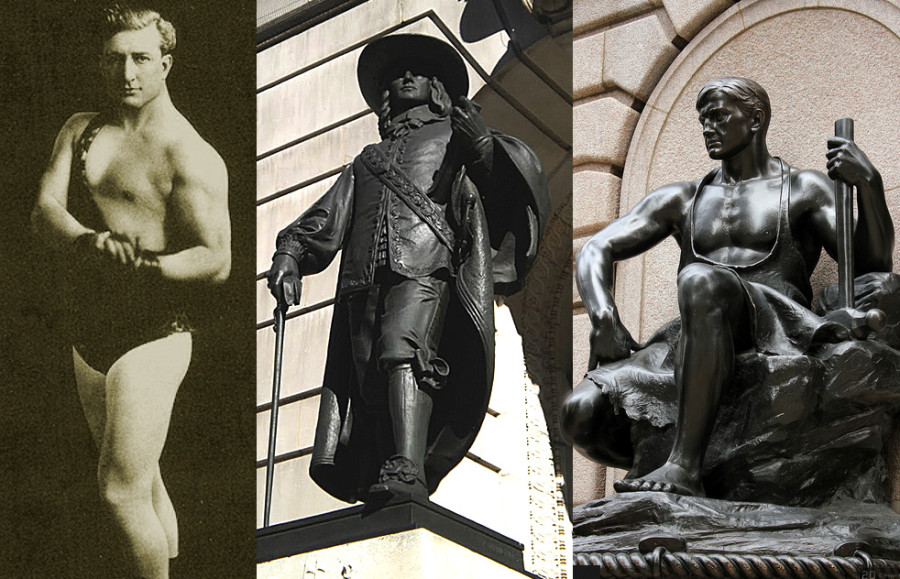

The world’s “first male sex symbol,” Baltimore’s Francis X. Bushman, got more than his allotted 15 minutes of fame. In fact, his image is still commanding respect today. Cast in bronze and chiseled in marble, he is likely to continue wowing the public for centuries to come.

Yes, that is Francis in his youthful prowess surveying his hometown as Cecilius Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, outside the Court House on St. Paul Street. That is also him as Francis Scott Key atop the memorial at 1300 Eutaw Place, and as a Confederate soldier in the Civil War monument at Charles Street and Wyman Park Drive near 29th Street.

As a young man, Bushman was a popular local model over at the Charcoal Club and the Maryland Institute. But his physique and his commanding brow and jaw line soon brought him attention outside of his birth city.

Years before making his first silent film, he was invited to pose for artists in New York. Between 1905 and 1908, he posed for such noted sculptors as Augustus Saint Gaudens and Ulric H. Ellerhusen, and was a favorite with Daniel Chester French, world-renowned sculptor of the Abraham Lincoln statue for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Born January 10, 1883, Francis X. Bushman grew up wanting to excel at everything he did. Before he was 12, he had read all the classics in his father’s library, memorized whole speeches from Shakespeare, and “ran up” the scales on the family piano each morning to train his vocal cords.

He pursued odd jobs around his Argyle Avenue neighborhood and used his savings to buy Bernarr Macfadden’s “Encyclopedia of Physical Culture,” whose philosophy was that the “sex lure” was a divine force that made human beings godlike.

Bushman adopted Macfadden’s daily steps to building “a powerful physique” and went from modeling for local artists at 50 cents an hour to being able to relocate to New York City with his wife and young children.

His likeness is said to appear in more bronze and marble in more American cities than any man in history. He provided the torso of George Washington on Wall Street, and stands proudly as Nathan Hale on the campus of Harvard University.

He posed for the statue outside New York’s Public Library Building and for the massive work “Conception” unveiled in the rotunda of the Palace of Fine Arts at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. He also appears at various sites as Simon Bolivar, as a king, a Pope and an Indian chief carved into a mountaintop in Appalachia.

Along the way, Bushman parlayed a string of small stage roles into a career as a movie star, working for the Essanay Film company of Chicago from 1911 until jumping to the Metro Company in 1915.

By 1918, he had starred in two hundred films and was earning a million dollars a year. With his wavy brown hair and athlete’s bearing, there were few who would challenge his billing as “the handsomest man in the world.”

Lavender was his favorite color. He was famous for smoking custom-made cigarettes wrapped in lavender paper, and he rode around Hollywood in a lavender Marmon luxury car with a small spotlight fixed on his profile and his name embossed in gold on both sides of the limousine.

It all came crashing down, though, when he was caught in an affair with his “Romeo and Juliet” costar, Beverly Bayne. The newspapers learned he also had a wife and five children back in Baltimore on an estate in Green Spring Valley they named Bushmanor.

The marriage ended shortly after, and Francis married his Juliet. But female moviegoers had already moved along to a new breed of “softer” sex symbol represented by Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert.

Bushman’s contract with Metro was part of the baggage included in the studio shuffle that re-organized as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. When he was cast in “Ben-Hur” as Messala, the villainous Roman officer, movie magazines called it a potential “comeback” role for the former matinee idol.

“The old man” is how gossip columnists and just about everyone else was calling Francis X. Bushman in 1925. He was, after all, forty-two years old.

Find out more about Francis X. Bushman and the bizarre fate of many of the others involved in the making of “Ben-Hur” in “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games.'” It’s available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Lulu Press.

(c) John W. Harding 2015

Betty

Wonderful article and you captured him so well.

John Harding

Thank you, Betty. It has been such a pleasure for me getting to know others interested in early motion pictures.

Kaedn

Keep these arctlies coming as they’ve opened many new doors for me.