The history of labor relations in the motion picture industry throughout the silent film era is still not widely known — and for good reason. It was the one subject that Hollywood itself sought to suppress.

This greater silence surrounding silent films eventually focused my research on the pivotal year of 1925, the setting of my fact-based novel, “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games.’” No sooner had motion pictures found a cozy home in Southern California than Los Angeles became a hotbed of labor unrest.

The thing that early film producers had found so attractive about L.A. — apart from the copious sunshine, of course — was that it was known as an “open-shop” city. In 1911, two union men named John and James McNamara pleaded guilty to bombing the offices of the notoriously antilabor Los Angeles Times. But if that criminal act momentarily set back the labor movement, it did not stop it for long.

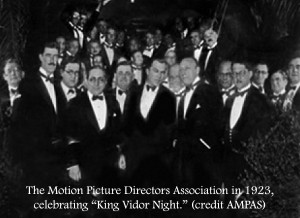

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) moved to sign up Hollywood craftspeople, but the studios tried to head them off by creating their own “closed-shop” alliances with producers. The Motion Picture Producers Association was first in 1917, followed by the Motion Picture Producers of America (an MPAA precursor) and the Motion Picture Directors Association. These were not guilds or unions, really, but attempts to “maintain the honor and dignity” of the industry and to “aid and assist all worthy distressed members.”

These studio-backed organizations were meant to avert strikes, like the one by studio craftsmen in July 1918 and another in 1921 over proposed wage reductions. Such labor actions, though, were mere coming attractions trailers for the massive studio-wide shutdown planned for 1926.

That was narrowly averted when producers and worker representatives signed the first Studio Basic Agreement — a milestone in Hollywood labor relations. The date was November 29, 1926, only a matter of months after the successful nationwide release of “Ben-Hur.”

To the general public, the announcement of a signed agreement must have come like a bolt from the blue. The specter of spiteful workers and union strife did not jibe with its image of Hollywood as the chic and sophisticated glamour capital of the world. It was not really a surrender to unions, however. Creative rights were not being given away, and the big labor battles still lay ahead.

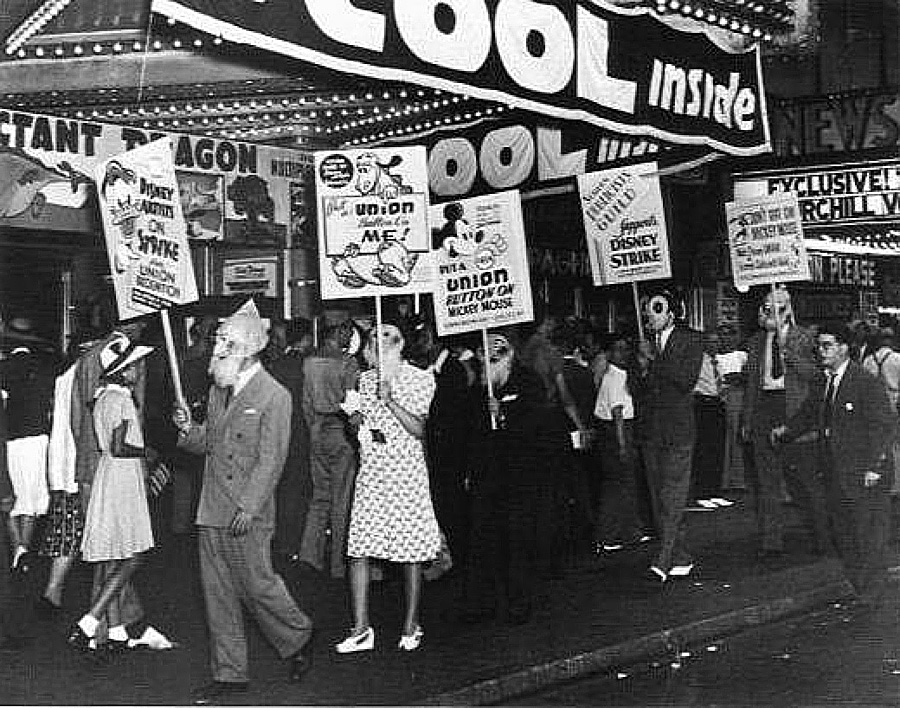

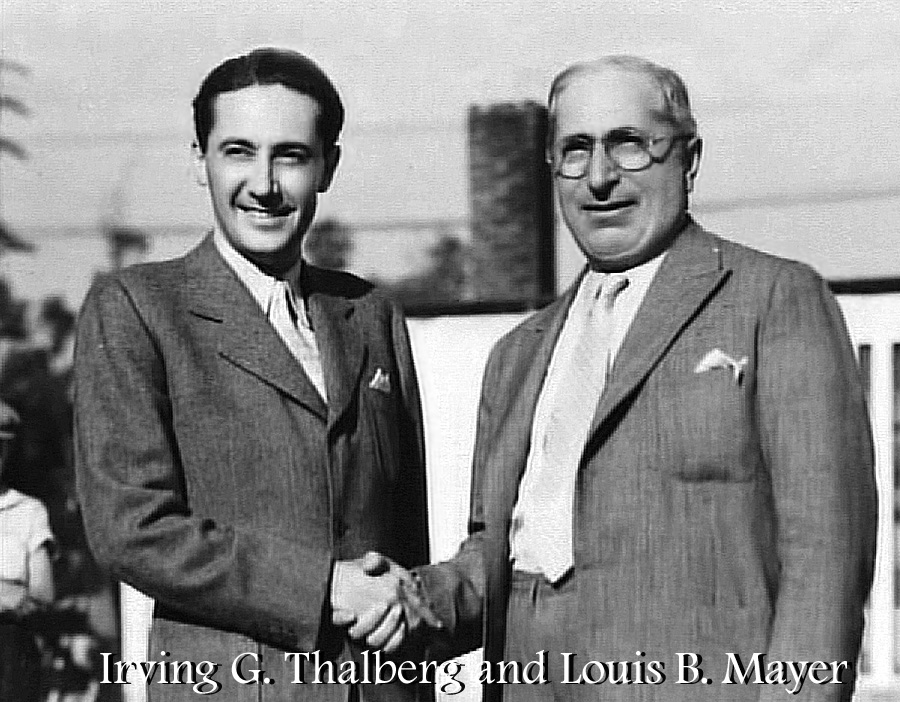

Today we associate motion picture unions more with the 1930s and 1940s. It was in 1933 when MGM wunderkind Irving Thalberg butted heads with the Screen Writers Guild. “Those writers are living like kings,” he reportedly said. “Why on Earth would they want to join a union like coal miners or plumbers?” In the shadow of the so-called “Red Scare,” police armies were on call, and even the revered Walt Disney Studios faced acrimonious labor strikes — a picket line one wag dubbed “truly animated.”

The truth is, film executives from the dawn of cinema had done everything they could to keep their labor battles out of the press and off the screens. Even while giving strong voice to a myriad of societal ills, early silent films remained consciously mute on the subject of their own labor problems.

Early unions

Long before any foundations were laid for the “Dream Factory” in California, union pressure was being applied to movie producers in the East. Filmmaking pioneers like Thomas Edison, Henry Marvin, William Selig and George Kleine all drew their skilled technicians from big-city trade unions. Engineers, carpenters, electricians, stage actors and directors, theatrical set designers and producers were all members of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees by the start of the 1900s.

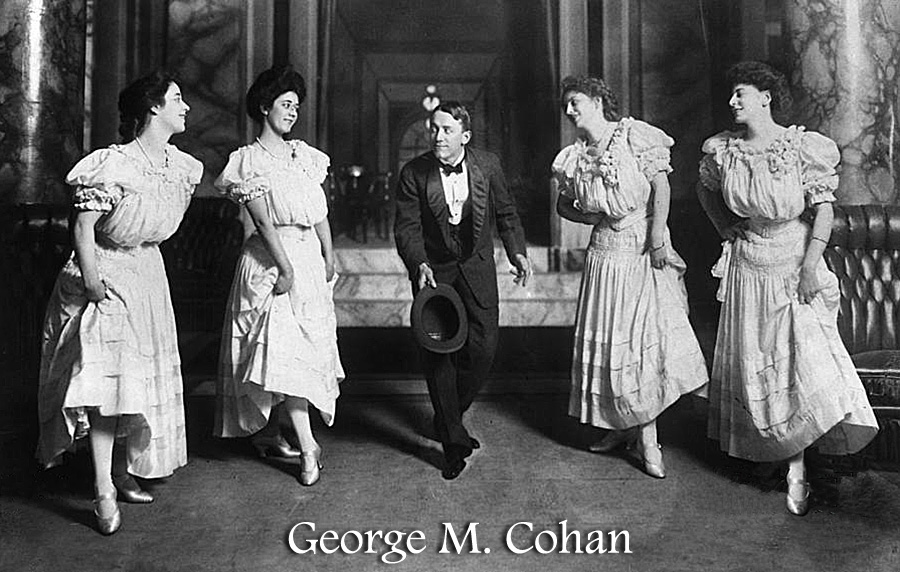

Ragtag groups existing outside of union reach had no defined rights or benefits. When disgruntled vaudeville performers in Manhattan known as “The White Rats” organized to challenge the unfair policies of vaudeville house managers and producers, legendary showman George M. Cohan sided against them. He said the performers had no claim on employee rights established for legit union members.

That same brand of elitism shielded the early movie studios in New York, New Jersey and Chicago from union demands. The so-called “flickers,” it was said, did not belong to the “legitimate” theater establishment. Silent movies were a cheap novelty and a fad. Actors who stooped to pick up quick cash as “models” for the moving pictures while “at liberty” often saw their value to stage producers plummet. As to other moonlighting tradesmen: One can only imagine the scorn heaped upon a Broadway set designer or stage electrician asking for union scale from a shoestring film outfit in Flatbush.

For their part, studio heads had survived the Edison “patent wars,” the competition from unlicensed independent film companies, and the chaotic first years of the film exchanges. They saw nothing wrong with setting up their own unions in the form of monopolistic trusts to regulate rental fees, fix exhibitor standards, control foreign distribution, protect copyrights and drive rivals out of business. But they adamantly opposed paying anyone a union wage.

The early 20th century was marked by the rise of organized anti-capitalist violence. On March 28, 1908, an anarchist set off a bomb at Union Square just two blocks from the Biograph Studios. Anarchism and the limits of social protest would become a recurring theme in Biograph movies under D.W. Griffith from 1908 through 1913.

A flicker of fame

While covering the battle for union benefits in the vaudeville industry, the entertainment media of the early 1900s paid no notice at all to the “filmed entertainments” of the day. Moving pictures were deemed a dubious diversion, best suited to Bowery rowdies and the influx of poor, non-English-speaking immigrants.

Things changed, though, when the New York Times began to review the one- and two-reel wonders opening at the growing numbers of five-cent theaters.

In her book “When the Movies Were Young,” Linda (Arvidson) Griffith, the actress-wife of D.W. Griffith, remembered the first film review she ever saw in print. It was October 10, 1909, the day after Biograph Studios opened its literary adaptation of “Pippa Passes”:

“It was all too much — much too much. The newspapers were writing about us,” she recalled. “It seemed incredible, but there it was before our eyes. … We nearly wept. Suddenly everything was changed. Now we could begin to lift up our heads, and perhaps invite our lit’ry friends to our movies!”

Soon most new openings were being reviewed and even upcoming releases were getting mentions in smart columns. There was increased competition among studios to sign “name” Broadway actors for special productions, and some popular film actors whose names were purposely not advertized were becoming famous under nicknames such as “The Biograph Girl.”

Capitalism versus labor

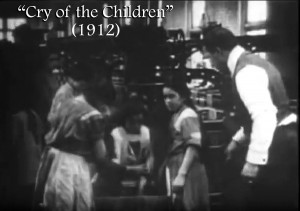

By 1910 some 26 million Americans each week were patronizing the nation’s nickelodeon theaters. They saw all manner of social ills addressed on screen: immorality, corruption, slavery, poverty, abortion, prostitution, racism, tainted meat-packing plants, capital punishment, gender inequality and more. The Thanhouser Studio’s “Cry of the Children” in 1912 powerfully exposed the subject of factories exploiting child labor.

There was a dynamic back-and-forth in the early years about the merits of capitalism versus socialism. Most early films argued for “fair play between employer and employee,” as Motion Picture World put it. Vitagraph’s “The Mill Girl — A Story of Factory Life” (1907) and “Capital vs. Labor” (1910), Selig’s “The Power of Labor” (1908), and Thanhouser’s “The Girl Strike Leader” (1910) often showed sympathetic employees standing up against the heartless greed of factory bosses.

Such tracts flew in the face of national headlines, which were more typically sympathetic to National Guard action taken against striking workers. Indeed, some studio cameramen picked up extra money filming picket lines for employers so that the strikes’ ringleaders could be identified for dismissal.

Among films favorable to capitalism was Thanhouser’s 1914 drama, “The Strike.” It argued the case for arbitration but did not flinch from showing how a dispute can get out of hand. When a worker is shown fired for incompetence, the union rallies and a hothead sets off a bomb inside the factory. The disheartened owner stands in the rubble and decides not to rebuild, leaving the community without the prospect of jobs.

At its convention in 1910, delegates from the American Federation of Labor called for a boycott of movie theaters showing films with themes that were hostile to the cause of labor. But in truth the industry was surprisingly even-handed — except when it came to its own employee practices.

While film companies exposed abuses at iron mills, coal mines, textile factories, fisheries and wheat combines, they had nothing at all to report on slave-wage carpenters, marathon work days, unaccredited screenwriters, crippled stunt men, drowned extras, disposable contract stars, sexually abused actresses, unsafe working conditions or other labor grievances within their own ranks.

It was with this background that the movies migrated cross-country to California, and set up shop in a city known to be fiercely pro-management and anti-union.

Hollywood in the 1920s

The first big-studio moguls were by and large immigrants who knew of the horrible scars left by poverty, squalor and czarist contempt. That made them liberals by nature, sympathetic to the underdog. But they now struggled to build an industry they found vulnerable to rivals and enemies, and at the mercy of a shifting public favor and fickle economic forces. That made them conservatives.

How did they so quickly come around to signing that 1926 Studio Basic Agreement? Ultimately, it was in their best interest to avoid death “by a million cuts” from lawyers, legislators and worker organizations.

In “The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games,’” I wanted to capture all the tumult of that transitional time. The silent film industry was in its final blush of hubris, and few could ignore the signs of change coming.

Sound technology was being adapted to film, just as radio had come into homes. The public wanted to hear the voices of their national leaders and their sports idols and film stars. Prohibition was in full swing, and that was having a profound effect on the way business was run inside the Hollywood studios. More than anything, though, there was a growing sense that the tough self-reliance of the film pioneers had to give way to more humane policies.

Early on in “The Ben-Hur Murders,” a young MGM horse wrangler comes upon a man who has been locked inside an outhouse. He frees the door and it turns out the man is a union organizer, with unseen enemies at large. When the union man attempts to distribute handbills for an upcoming meeting, one of the old-time studio cowboys drops the pile on an open campfire. “If I wanted to live on a reservation I’d become an Indian,” he says.

During the long, deadly course of that day, both the pro- and anti-union attitudes of the men are exposed. Some see the need of a union to oversee workplace safety and give individuals a place to air their grievances. Others see it as a surefire way to strangle the goose laying the golden eggs. When deadly accidents begin to mount, some see these as evidence of studio indifference, while others see them as acts of sabotage by union agitators. It is a divisive issue very much in the air, very much unsettled.

Most of the hired men despise the cavalier attitude toward the welfare of animals on the set. They may suspect that their own health and the honor of their sisters is of little more concern to those in charge. Anyone can end up injured or exploited and then brushed aside in a one-industry town like 1925 Hollywood.

On the other hand, MGM had just ended a protracted and costly experience of filming in Italy. Executives and employees both had witnessed life under Mussolini, from the recurrent labor stoppages and bureaucratic meddling to gross mismanagement by junior officials. There had been numerous deaths on the Italian locations due to the pressures of trying to make up for so much lost time. Finally, they had come home to Culver City chastened, resolving never to repeat the mistakes of Italy.

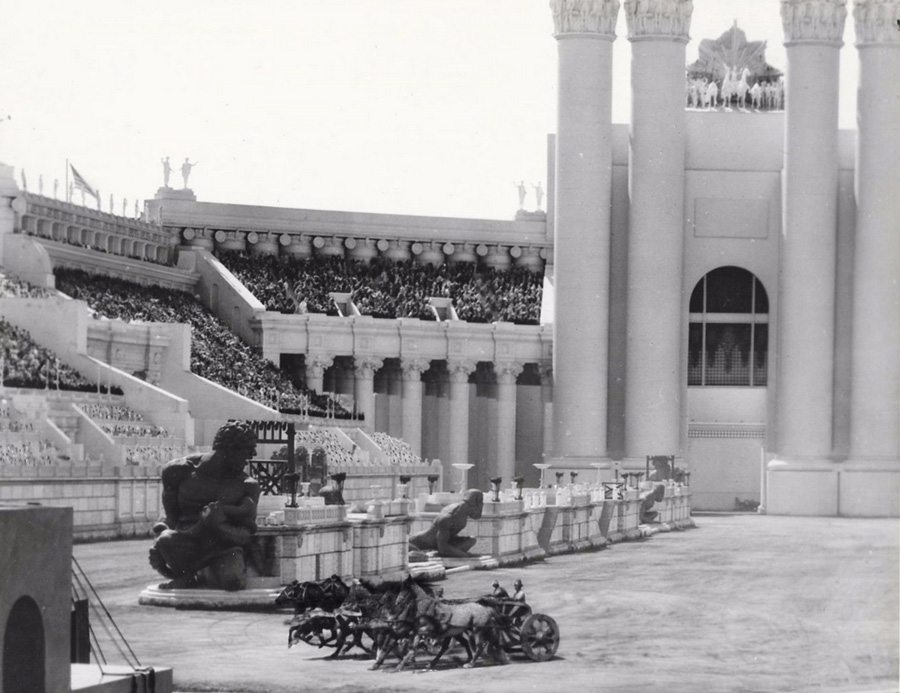

I am convinced that the pressures piled on production head Irving Thalberg to get “Ben-Hur” finished prompted his near-fatal heart attack the day before Thanksgiving, 1925. As late as October 17, the studio was shooting all the major crowd scenes for the chariot race, and the picture had already been booked into Sid Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood as its big Christmas attraction. Thalberg was forced to view rushes projected on his hospital room ceiling because he was too sick to sit up.

After the critical and box office triumph of “Ben-Hur,” both Thalberg and MGM studio head Louis Mayer were for a time revered figures in Hollywood. Many other chiefs looked to Mayer for leadership, and Mayer had a great fatherly affection for Irving. I am just novelist enough to think that Thalberg’s close brush with death was enough of a reminder of life’s brevity to nudge Mayer closer to leading all of his fellow executives to signing that 1926 Studio Basic Agreement with workers’ representatives. Whether or not that is true, the rest is history.

(c) 2016 John W. Harding

“The Ben-Hur Murders: Inside the 1925 ‘Hollywood Games’” is available at Amazon.com as a paperback and Kindle download, and exclusively in hardcover at Lulu Press.

monster legends hack download

Really fine post, I definitely adore this website, keep on it.